Marine Life & Conservation Blogs

Creature Feature: Manta Rays

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

This month they’re showcasing the largest rays in the world. Made up of 2 different species, these captivating giants are highly intelligent. And, come in a range of unusual colours!

The word ‘manta’ is Spanish for blanket or cloak, which perfectly describes the body-shape of a manta ray. These enormous, flat, diamond-shaped animals, have wingspans stretching up to 7m wide and can weigh up to 1,350kg.

Mantas also have 2 horns at the front of their head, giving them the nickname ‘devil fish’. But there’s nothing devilish about these gentle giants. Or their close cousins the devil rays, who often get confused for mantas. Both, use their ‘horns’ (or cephalic fins) during feeding to scoop up tiny plants and animals in the water. Similar to how we use a spoon to eat soup. Their cephalic fins may also play a role in sensing their environment and during social interactions.

Just like the Basking and Whale Shark, manta rays are filter feeders. Swimming with their mouths wide open, they suck in huge volumes of water – rich in zooplankton. Their tiny prey is then filtered through gill plates that line their mouth. Sadly, these gill plates are highly sought after in the Chinese medicinal trade, which has led to mantas being heavily over-fished.

As any diver can attest, seeing a manta in the wild is a pure delight. Their elegance and grace in the water is unrivaled. Particularly at feeding time. Mantas need to keep moving to breathe, so individuals will perform multiple somersaults to stay in a single spot where there’s lots of food. Like a perfectly orchestrated dance, mantas will also follow each other in a circle to chain-feed. Their movements expertly creating a vortex that traps their prey inside.

Manta Rays live in tropical, subtropical, and temperate waters around the world. They tend to live on their own or in small groups. But will often gather in large groups to feed. Hotspots for this feeding behaviour include the Bahamas, Fiji, Indonesia, Thailand, Spain and the Maldives. And aggregations are known as a squadron of manta ray.

In 2008, scientists discovered that the Manta Ray, which was once thought of as a single species, was in fact two different species. The Giant Oceanic Manta Ray (Mobula birostris) and the much smaller Reef Manta Ray (Mobula alfredi). Both species were formerly classified under the separate genus Manta. But following genetic testing in 2017, scientists discovered they were more closely related to devil rays (genus Mobula) than previously thought and reclassified them as such.

The Giant Manta is widespread, spending most of their time far from land in open ocean. While the Reef Manta tends to prefer the warmer coastal waters of the Indo-Pacific. Fully grown, the wingspan of a Giant Manta can reach up to 7m (typically 4.5m). While the largest wingspan for a Reef Manta is 5m (typically 3-3.5m). Both are dark in colour on top with a pattern of white lines. On the Giant Manta the white lines form a T shape, while on the Reef Manta they form a Y shape.

We can also identify each individual manta by their unique markings. Found on the underside of their body (between the gills and on their bellies), these act just like a human fingerprint. Enabling scientists to use photo-ID to discover more about them.

Manta Rays regularly visit cleaning stations, like many other marine animals, often returning to the same spot. Here smaller animals groom them, removing pesky parasites and dead skin. These spa trips to the coral reef provide researchers with the perfect opportunity to photograph and study them in the wild.

In Raja Ampat, researchers have discovered an unusual group of Reef Mantas, affectionately known as the ninja warriors. This area has the highest percentage of melanistic (black) Reef Mantas in the world. Usually melanistic mantas comprise around 10% of a population, but here they represent 40%. This genetic trait is inherited and doesn’t appear to affect their survival rate.

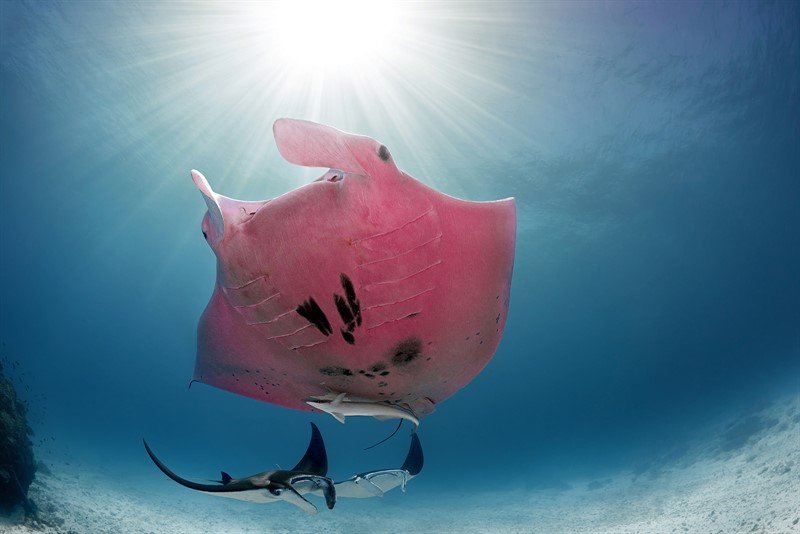

If you visit the Great Barrier Reef, you may witness an even more astounding sight…

A 3m male Reef Manta named ‘Inspector Clouseau’, who also happens to be bright PINK! Big thanks to Kristian Laine Photography for providing the incredible photo above.

The Inspector is the only known pink manta in the world. His rosy hue is believed to be the result of a condition called erythrism – a genetic mutation in melanin production. Again, this doesn’t seem to impact his survival. Indeed, he’s been spotted a handful of times since his first debut in 2015, so is doing well.

Highly intelligent, these majestic animals have the largest brain to body weight ratio of any fish. Studies suggest they have high cognitive function – similar to dolphins, primates and elephants – and excellent long-term memory.

Due to their large size, adult mantas don’t have many natural predators. Although, larger sharks and orca have been known to prey on them. Yet, the biggest threat they face comes from humans. Due to their low reproductive rate mantas are incredibly vulnerable to over-fishing.

These long-living animals are thought to live up to 50 years. Giving birth every 4-5 years, they’ll only produce between 4-7 pups during their lifetime.

GIANT MANTA RAY:

- SCIENTIFIC NAME: Mobula birostris

- FAMILY: Mobulidae (Manta & Devil Rays)

- MAXIMUM SIZE: 7m

- DIET: Zooplankton, krill & small fish.

- DISTRIBUTION: Worldwide in tropical and temperate waters. Found from the surface to depths of 1,000m.

- HABITAT: Spends long periods of time in the open ocean. Visits shallow coastal waters near coral and rocky reefs.

- CONSERVATION STATUS: Endangered

REEF MANTA RAY:

- SCIENTIFIC NAME: Mobula alfredi

- FAMILY: Mobulidae (Manta & Devil Rays)

- MAXIMUM SIZE: 5m

- DIET: Zooplankton, krill & small fish.

- DISTRIBUTION: Tropical and sub-tropical waters of the Indian and Pacific Ocean. Found from the surface to depths of 432m.

- HABITAT: Shallow coastal waters near coral and rocky reefs. Moves into deeper waters at night to feed.

- CONSERVATION STATUS: Vulnerable

Header Image: Frogfish Photography

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs

Creature Feature: Dusky Shark

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

This month we’re taking a look at the Dusky Shark, a highly migratory species with a particularly slow growth rate and late age at maturity.

Dusky sharks are one of the largest species within the Carcharhinus genus, generally measuring 3 metres total length but able to reach up to 4.2 metres. They are grey to grey-brown on their dorsal side and their fins usually have dusky margins, with the darkest tips on the caudal fin.

Dusky Sharks can often be confused with other species of the Carcharhinus genus, particularly the Galapagos Shark (Carcharhinus galapagensis). They have very similar external morphology, so it can be easier to ID to species level by taking location into account as the two species occupy very different ecological niches – Galapagos Sharks prefer offshore seamounts and islets, whilst duskies prefer continental margins.

Hybridisation:

A 2019 study found that Dusky Sharks are hybridising with Galapagos Sharks on the Eastern Tropical Pacific (Pazmiño et al., 2019). Hybridisation is when an animal breeds with an individual of another species to produce offspring (a hybrid). Hybrids are often infertile, but this study found that the hybrids were able to produce second generation hybrids!

Long distance swimmers:

Dusky sharks are highly mobile species, undertaking long migrations to stay in warm waters throughout the winter. In the Northern Hemisphere, they head towards the poles in the summer and return southwards towards the equator in winter. The longest distance recorded was 2000 nautical miles!

Very slow to mature and reproduce:

The Dusky Shark are both targeted and caught as bycatch globally. We already know that elasmobranchs are inherently slow reproducers which means that they are heavily impacted by overfishing; it takes them so long to recover that they cannot keep up with the rate at which they are being fished. Dusky Sharks are particularly slow to reproduce – females are only ready to start breeding at roughly 20 years old, their gestation periods can last up to 22 months, and they only give birth every two to three years. This makes duskies one of the most vulnerable of all shark species.

The Dusky Shark is now listed on Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species (CMS), but further action is required to protect this important species.

Scientific Name: Carcharhinus obscurus

Family: Carcharhinidae

Maximum Size: 420cm (Total Length)

Diet: Bony fishes, cephalopods, can also eat crustaceans, and small sharks, skates and rays

Distribution: Patchy distribution in tropical and warm temperate seas; Atlantic, Indo-Pacific and Mediterranean.

Habitat: Ranges from inshore waters out to the edge of the continental shelf.

Conservation status: Endangered.

For more great shark information and conservation visit the Shark Trust Website

Images: Andy Murch

Diana A. Pazmiño, Lynne van Herderden, Colin A. Simpfendorfer, Claudia Junge, Stephen C. Donnellan, E. Mauricio Hoyos-Padilla, Clinton A.J. Duffy, Charlie Huveneers, Bronwyn M. Gillanders, Paul A. Butcher, Gregory E. Maes. (2019). Introgressive hybridisation between two widespread sharks in the east Pacific region, Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 136(119-127), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2019.04.013.

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs

Creature Feature: Undulate Ray

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

This month we’re looking at the Undulate Ray. Easily identified by its beautiful, ornate pattern, the Undulate Ray gets its name from the undulating patterns of lines and spots on its dorsal side.

This skate is usually found on sandy or muddy sea floors, down to about 200 m deep, although it is more commonly found shallower. They can grow up to 90 cm total length. Depending on the size of the individual, their diet can range from shrimps to crabs.

Although sometimes called the Undulate Ray, this is actually a species of skate, meaning that, as all true skates do, they lay eggs. The eggs are contained in keratin eggcases – the same material that our hair and nails are made up of! These eggcases are also commonly called mermaid’s purses and can be found washed up on beaches all around the UK. If you find one, be sure to take a picture and upload your find to the Great Eggcase Hunt – the Shark Trust’s flagship citizen science project.

It is worth noting that on the south coasts, these eggcases can be confused with those of the Spotted Ray, especially as they look very similar and the ranges overlap, so we sometimes informally refer to them as ‘Spundulates’.

Scientific Name: Raja undulata

Family: Rajidae

Maximum Size: 90cm (total length)

Diet: shrimps and crabs

Distribution: found around the eastern Atlantic and in the Mediterranean Sea.

Habitat: shelf waters down to 200m deep.

Conservation Status : As a commercially exploited species, the Undulate Ray is a recovering species in some areas. The good thing is that they have some of the most comprehensive management measures of almost any elasmobranch species, with both minimum and maximum landing sizes as well as a closed season. Additionally, targeting is entirely prohibited in some areas. They are also often caught as bycatch in various fisheries – in some areas they can be landed whilst in others they must be discarded.

IUCN Red List Status: Endangered

For more great shark information and conservation visit the Shark Trust Website

Image Credits: Banner – Sheila Openshaw; Illustration – Marc Dando

-

News3 months ago

News3 months agoHone your underwater photography skills with Alphamarine Photography at Red Sea Diving Safari in March

-

News3 months ago

News3 months agoCapturing Critters in Lembeh Underwater Photography Workshop 2024: Event Roundup

-

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs3 months ago

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs3 months agoCreature Feature: Swell Sharks

-

Blogs2 months ago

Blogs2 months agoMurex Resorts: Passport to Paradise!

-

Blogs2 months ago

Blogs2 months agoDiver Discovering Whale Skeletons Beneath Ice Judged World’s Best Underwater Photograph

-

Marine Life & Conservation2 months ago

Marine Life & Conservation2 months agoSave the Manatee Club launches brand new webcams at Silver Springs State Park, Florida

-

Gear Reviews3 months ago

Gear Reviews3 months agoGear Review: Oceanic+ Dive Housing for iPhone

-

Gear Reviews2 weeks ago

Gear Reviews2 weeks agoGEAR REVIEW – Revolutionising Diving Comfort: The Sharkskin T2 Chillproof Suit