Marine Life & Conservation Blogs

Creature Feature: Big Skate

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

This month we’re focusing on the Big Skate, a species which might just have the most self-explanatory of all common names. It’s big and it’s a skate.

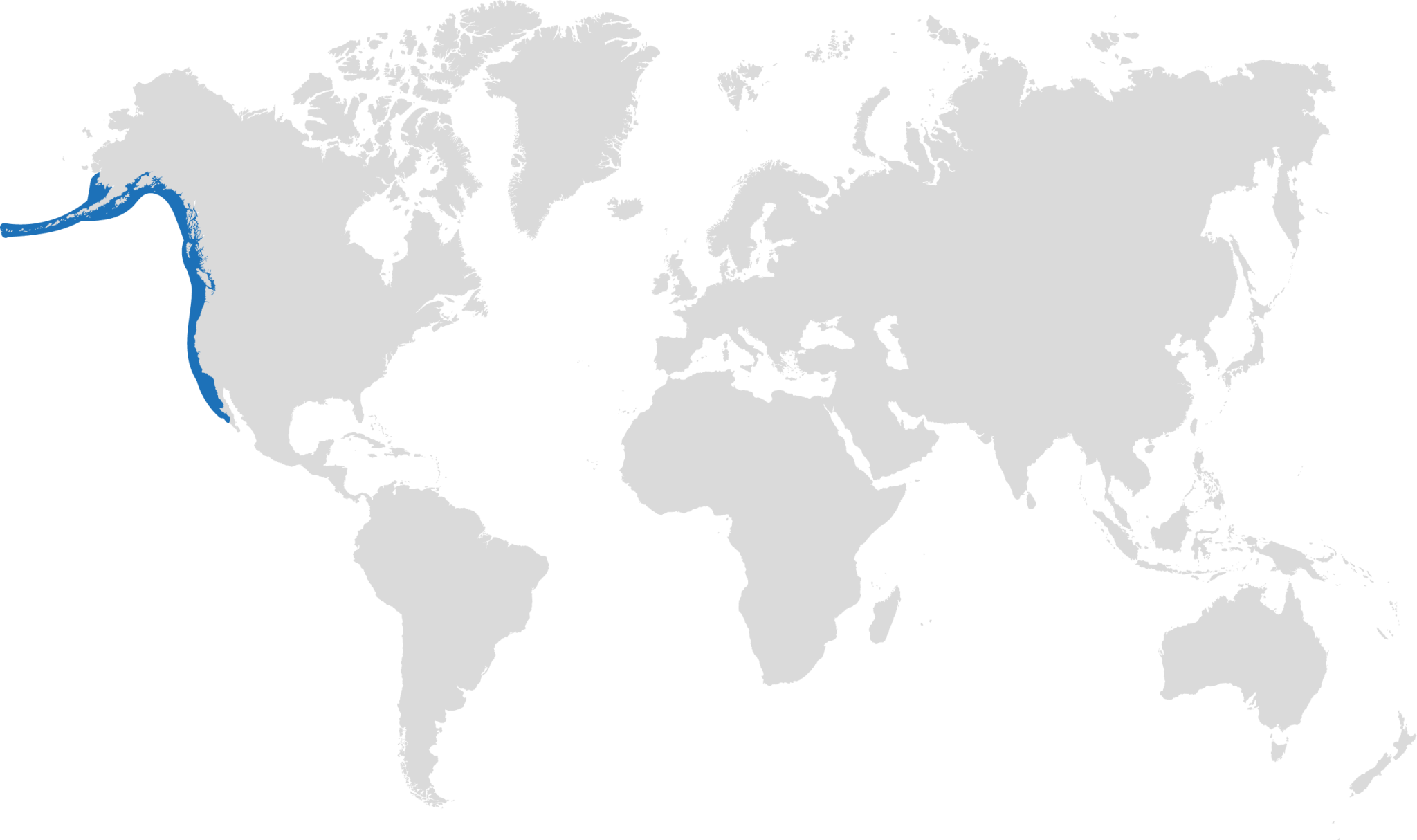

The largest species of skate in North American waters, the largest Big Skate (Beringraja binoculata) on record was measured to be 2.4m long! Found only in the north-eastern Pacific Ocean, these skate can be found at depths anywhere between 3-800m, although they are more commonly found shallower. Big Skate have a distinctive diamond-shaped body and likely have the largest eggcases in the Rajidae family, measuring 22.8-30cm long!

In addition to their great size, their eggcases are remarkable because they usually contain 3-4 embryos (up to 8!), making them one of the only species of elasmobranch to contain multiple embryos in their eggcases! They have been known to produce up to 360 eggcases per year in captivity. Now let’s assume an average of 3.5 embryos per eggcase, then in one year, they have the potential to produce 1,260 babies! It is therefore one of the most reproductive of all elasmobranchs[1]. In the wild of course, not all of the embryos would be successful due to predation and other natural factors. Elephant seals have sometimes been recorded to eat Big Skate eggcases.

Like many other species of skate, they have large ‘eyespots’ on the pectoral fins which are thought to be used to deceive predators and make them more hesitant to attack. This is a form of mimicry and can be found in butterflies, reptiles, cats, birds and fish. A great example are the eyespots on the feathers of peacocks!

One theory behind their function is that the resemblance of the eyespots to the eyes of predators’ own predators produces an intimidating effect[2]. But other theories argue that it is simply how noticeable they are to predators that stimulates avoidance behaviour[3]. Other studies have found that it can be a form of ‘self-mimicry’, wherein the eyes draw the predator’s attention away from its most vulnerable body parts. They can also play a role in courtship behaviours.

Scientific Name: Beringraja binoculata

Family: Rajidae

Maximum Size: 290cm (total maximum length)

Diet: Marine invertebrates such as shrimps, worms and clams, sometimes small fish.

Distribution: North-eastern Pacific Ocean, from Alaska to Baja California.

Habitat: At depths of 3-800m. Commonly founder shallower – between 100-200m in sandy/muddy coastal bays and estuaries.

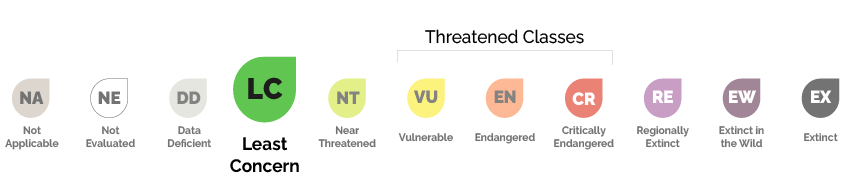

Conservation Status: In general, the Big Skate is not a major fishery target, although there are commercial and recreational fisheries in Californian waters where it is commonly landed as bycatch. Together with Longnose Skate*, these two species account for 99% of the skate landings in British Columbia[4]. They are currently listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List, however there are a lack of species-specific stock assessments in certain areas, and so this is just an estimate.

IUCN Red List Status: Least Concern

*Note, the common name ‘Longnose Skate’ can refer to several species of skate. In northeast Atlantic and Mediterranean waters, it refers to Dipturus oxyrinchus. In southeastern Australian coasts, the skate is Dentiraja confusa. In the northeast Pacific, the name refers to Beringraja rhina.

For more great shark information and conservation visit the Shark Trust Website

Photo Credits: Andy Murch

[1] Wallace, S. (2006). Seafood Assessment: Longnose Skate and Big Skate Raja rhina and Raja binoculata. SeaChoice. Blue Planet Research and Education.

[2] Karin Kjernsmo et al. Resemblance to the Enemy’s Eyes Underlies the Intimidating Effect of Eyespots, The American Naturalist (2017). DOI: 10.1086/693473

[3] Martin Stevens, Chloe J. Hardman, Claire L. Stubbins, Conspicuousness, not eye mimicry, makes “eyespots” effective antipredator signals, Behavioral Ecology, Volume 19, Issue 3, May-June 2008, Pages 525–531, https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arm162

[4] Wallace, S. (2006). Seafood Assessment: Longnose Skate and Big Skate Raja rhina and Raja binoculata. SeaChoice. Blue Planet Research and Education.

Blogs

Invitation from The Ocean Cleanup for San Francisco port call

6 years ago, The Ocean Cleanup set sail for the Great Pacific Garbage Patch with one goal: to develop the technology to be able to relegate the patch to the history books. On 6 September 2024, The Ocean Cleanup fleet returns to San Francisco bringing with it System 03 to announce the next phase of the cleanup of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch and to offer you a chance to view our cleanup system up-close and personal.

We look forward to seeing you there.

To confirm your presence, please RSVP to press@theoceancleanup.com

PROGRAM

Join The Ocean Cleanup as our two iconic ships and the extraction System 03 return to San Francisco, 6 years and over 100 extractions after we set sail, to create and validate the technology needed to rid the oceans of plastic.

Our founder and CEO, Boyan Slat, will announce the next steps for the cleanup of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Giving you a chance to view our cleanup system and the plastic extracted.

Hear important news on what’s next in the mission of The Ocean Cleanup as it seeks to make its mission of ridding the world’s oceans of plastic an achievable and realistic goal.

Interviews and vessel tours are available on request.

PRACTICALITIES

Date: September 6, 2024

Press conference: 12 pm (noon)

Location: The Exploratorium (Google Maps)

Pier 15 (Embarcadero at Green Street), San Francisco, CA

Parking: Visit The Exploratorium’s website for details.

RSVP: press@theoceancleanup.com

Video & photo material from several viewing spots around the bay

We look forward to seeing you there!

ABOUT THE OCEAN CLEANUP

The Ocean Cleanup is an international non-profit that develops and scales technologies to rid the world’s oceans of plastic. They aim to achieve this goal through a dual strategy: intercepting in rivers to stop the flow and cleaning up what has already accumulated in the ocean. For the latter, The Ocean Cleanup develops and deploys large-scale systems to efficiently concentrate the plastic for periodic removal. This plastic is tracked and traced to certify claims of origin when recycling it into new products. To curb the tide via rivers, The Ocean Cleanup has developed Interceptor™ Solutions to halt and extract riverine plastic before it reaches the ocean. As of June 2024, the non-profit has collected over 12 million kilograms (26.4 million pounds) of plastic from aquatic ecosystems around the world. Founded in 2013 by Boyan Slat, The Ocean Cleanup now employs a broadly multi-disciplined team of approximately 140. The foundation is headquartered in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and opened its first regional office in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, in 2023.

Find out more about The Ocean Cleanup at www.theoceancleanup.com.

Blogs

Smart Shark Diving: The Importance of Awareness Below the Surface

By: Wael Bakr

Introduction to Shark Diving Awareness

In the realm of marine life, few creatures captivate our interest, and sometimes our fear, like the shark. This fascination often finds a home in the hearts of those who venture beneath the waves, particularly scuba divers who love shark diving. It’s here that shark awareness takes the spotlight. Shark awareness is not just about understanding these magnificent creatures; it’s about fostering respect, dispelling fear, and promoting conservation. As Jacques Cousteau once said, “People protect what they love.” And to love something, one must first understand it.

Shark awareness is not a mere fascination; it’s a responsibility that we owe to our oceans and their inhabitants. From the smallest reef shark to the colossal great white, each species plays a crucial role in the underwater ecosystem. Our understanding and appreciation of these creatures can help ensure their survival.

However, shark awareness isn’t just about protecting the sharks; it’s also about protecting ourselves. As scuba divers, we share the underwater world with these magnificent creatures. Understanding them allows us to dive safely and responsibly, enhancing our experiences beneath the waves.

Importance of Shark Awareness in Scuba Diving

The relevance of shark awareness in scuba diving cannot be overstated. Sharks, like all marine life, are an integral part of the underwater ecosystem. Their presence and behavior directly influence our experiences as divers. By understanding sharks, we can better appreciate their role in the ocean, anticipate their actions, and reduce potential risks.

Awareness is crucial for safety when shark diving. Despite their often-misunderstood reputation, sharks are generally not a threat to humans. However, like any wild animal, they can pose risks if provoked or threatened. By understanding shark behavior, we can identify signs of stress or aggression and adjust our actions accordingly. This not only protects us but also respects the sharks and their natural behaviors.

Moreover, shark awareness enriches our diving experiences. Observing sharks in their natural habitat is a thrilling experience. Understanding them allows us to appreciate this spectacle fully. It’s not just about seeing a shark; it’s about understanding its role in the ecosystem, its behavior, and its interaction with other marine life. This depth of knowledge adds a new dimension to our diving experiences.

Understanding Shark Behavior: The Basics

The first step in shark awareness is understanding shark behavior. Sharks are not the mindless predators they are often portrayed to be. They are complex creatures with unique behaviors and communication methods. Understanding these basics can significantly enhance our interactions with them.

Sharks communicate primarily through body language. By observing their movements, we can gain insights into their mood and intentions. For example, a relaxed shark swims with slow, fluid movements. In contrast, a stressed or agitated shark may exhibit rapid, jerky movements or other signs of discomfort such as gill flaring.

Sharks also use their bodies to express dominance or assertiveness. A dominant shark may swim with its pectoral fins pointed downwards, while a submissive shark may swim with its fins flattened against its body. Understanding these signals can help us interpret shark behavior accurately and respond appropriately.

How Shark Awareness Enhances Scuba Diving Experiences

Shark awareness significantly enhances our scuba diving experiences. It transforms encounters with sharks from mere sightings into meaningful interactions. Knowledge is power, and in this case, it’s the power to appreciate, respect, and safely interact with one of the ocean’s most fascinating inhabitants.

A thorough understanding of behavior when shark diving allows us to interpret their actions and responses accurately. It enables us to recognize signs of stress or aggression and adjust our behavior accordingly. This not only ensures our safety but also promotes responsible interactions that respect the sharks and their natural behaviors.

Furthermore, shark awareness adds a new layer of depth to our diving experiences. It’s one thing to see a shark; it’s another to understand its behavior, its role in the ecosystem, and its interactions with other marine life. This depth of understanding enriches our experiences and fosters a deeper appreciation for our underwater world.

Misconceptions About Sharks: Busting the Myths

Unfortunately, sharks are often misunderstood, feared, and even demonized. These misconceptions can be detrimental, not only to our experiences as divers but also to shark conservation efforts. As part of shark awareness, it’s important to debunk these myths and present sharks in their true light.

First and foremost, sharks are not mindless killing machines. They are complex creatures with unique behaviors and communication methods. They are not interested in humans as prey and, in most cases, prefer to avoid us.

Secondly, not all sharks are dangerous. Out of over 500 species of sharks, only a handful are considered potentially harmful to humans. Most sharks are harmless, and even those that can pose a threat are unlikely to attack unless provoked.

Lastly, sharks are not invincible. They are vulnerable to a host of threats, most notably human activities such as overfishing and habitat destruction. They need our understanding and protection, not our fear and persecution.

Shark Behavior: What to Expect When Scuba Diving

When scuba diving, it’s important to know what to expect from sharks. Most encounters with sharks are peaceful and awe-inspiring. However, as with any wild animal, it’s essential to be prepared and understand their behavior.

Most sharks are shy and cautious creatures. They are likely to observe you from a distance, often circling around to get a better look. This is normal behavior and not a sign of aggression.

However, if a shark becomes agitated or feels threatened, it may exhibit signs of stress such as rapid, jerky movements or gill flaring. In such cases, it’s essential to remain calm, avoid sudden movements, and slowly retreat if possible.

Remember, every encounter with a shark is an opportunity to observe and learn. With understanding and respect, these encounters can be safe, enriching, and truly unforgettable experiences.

Practical Tips for Shark Awareness During Scuba Diving

Being aware of sharks during scuba diving is about more than just understanding their behavior. It’s about applying this knowledge in practical ways to ensure safe and respectful interactions. Here are a few tips for shark awareness during scuba diving.

Firstly, always observe sharks from a safe distance. Avoid approaching them directly or making sudden movements, as this can startle or threaten them.

Secondly, never attempt to touch or feed sharks. This can disrupt their natural behavior and potentially put you at risk.

Lastly, always respect the sharks and their environment. Avoid disturbing their habitat or interfering with their natural behaviors. Remember, we are visitors in their world.

Promoting Shark Conservation through Scuba Diving

Scuba diving offers a unique platform for promoting shark conservation. As divers, we have the privilege of witnessing the beauty and complexity of sharks firsthand. We can share these experiences with others, fostering understanding and appreciation for these magnificent creatures.

Moreover, we can actively contribute to shark conservation. Many diving operators offer opportunities to participate in shark research and conservation initiatives. By participating in these programs, we can help ensure the survival of sharks for future generations.

Lastly, we can advocate for sharks. By sharing our knowledge and experiences, we can help dispel misconceptions about sharks and promote their protection. Every voice counts in the fight for shark conservation.

Courses and Resources for Shark Awareness and Behavior

There are many resources available for those interested in shark awareness and behavior. Scuba Diving International as well as numerous conservation-based organizations offer courses and workshops on shark biology, behavior, and conservation. These courses provide in-depth knowledge and practical skills for interacting with sharks responsibly and safely. From courses like our Marine Ecosystems Awareness Specialty and our Advanced Adventure Certification provide you with the information you need to tackle this new challenge!

Additionally, there are many online resources available, including websites, blogs, and forums dedicated to shark awareness and conservation. These platforms offer a wealth of information and a community of like-minded individuals passionate about sharks.

I encourage anyone interested in sharks to explore these resources, to sign up for one of SDI’s courses call your local dive center or instructor or reach out to your regional representative/ World HQ to find where the class is being taught near you. Knowledge is the first step towards understanding, appreciation, and conservation.

Conclusion: The Role of Shark Awareness in Future Scuba Diving Experiences

As we look to the future, the role of shark awareness in scuba diving will only continue to grow. As our understanding of these magnificent creatures deepens, so too will our appreciation and respect for them. This knowledge will shape our interactions with sharks, enhancing our experiences and promoting responsible and respectful behavior.

Shark awareness is more than just an interest; it’s a responsibility. It’s a commitment to understanding, respecting, and protecting one of the ocean’s most fascinating inhabitants. And it’s a journey that I invite all divers to embark on.

As we dive into the blue, let’s dive with awareness. Let’s dive with respect. And let’s dive with a commitment to understand and protect our underwater world. For in the end, the ocean’s health is our health, and every creature within it, including the sharks, plays a crucial role in maintaining this delicate balance.

-

Blogs2 months ago

Blogs2 months agoDiving With… Nico, Ocean Earth Travels, Indonesia

-

News1 month ago

News1 month agoMurex Bangka Announce New Oceanfront Cottages & Beachfront Dining

-

Blogs2 months ago

Blogs2 months agoA new idea in freediving from RAID

-

Marine Life & Conservation1 month ago

Marine Life & Conservation1 month agoIceland issue millionaire whale hunter a licence to murder 128 vulnerable fin whales

-

Marine Life & Conservation2 months ago

Marine Life & Conservation2 months agoThe Shark Trust Great Shark Snapshot is back

-

News3 months ago

News3 months agoCharting New Waters; NovoScuba Goes Global with the Launch of their Revolutionary Dive Training Agency!

-

Gear News1 month ago

Gear News1 month agoNew Suunto Ocean – a dive computer and GPS sports watch in one for adventures below and above the surface

-

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs2 months ago

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs2 months agoBook Review: Plankton