Marine Life & Conservation Blogs

Earthdive – a global project to save our oceans (Part 2)

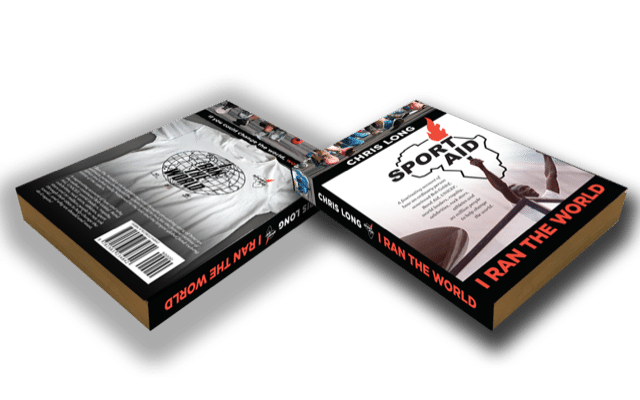

Jeff Goodman met Chris Long in an airport arrivals cafe where he told Jeff of his new project earthdive, a revolutionary concept in citizen science and a global research project for millions of recreational scuba divers, snorkellers and others who can help preserve the health and diversity of our oceans. Since then Chris has written “I Ran the World” challenging today’s young people to take up his baton.

Extract:

I Ran the World – If you could change the world, would you?

Chapter 20 – New Beginnings

I hadn’t been living life for long after Sport Aid when, driving through Luton one day, I passed a shop called Deep Dive.

It grabbed my attention.

I stopped the car, parked and strolled over to take a look.

Surely not.

Ever since I was about five years old I’d always wanted to be a diver. The underwater world had fascinated me. I loved Jacques Cousteau programmes as well as nature programmes involving the oceans, while my favourite James Bond was Thunderball, which was mostly shot underwater.

I also had a scary love of sharks.

As I walked closer to the shop I could see all manner of dive equipment hanging in the window. Masks, tanks, buoyancy jackets, everything a little frogman could want.

Why? This is nowhere near the sea?

A little bell rang as I walked in and a follically-challenged young man greeted me with a warm ‘Good morning.’

“Is this a scuba diving shop?”

He looked at me as if I were mad.

Er, yeah, what else could it be?

“Yes, recreational and technical diving. We supply equipment, fill tanks and run courses.”

“From here?”

It just seemed so incongruous that a scuba diving shop should be in a busy town centre miles from the sea. I explained that I’d always wanted to be a diver, how life had passed me by and that I’d never got the chance to do it.

I rattled on about my very first job interview as a research assistant at the Royal Naval Physiological Laboratory in Gosport, Hampshire. I could even remember the advert in the paper.

To work on ‘breathing limitations in diving.’

I even remembered the interview.

I said I’d played football and was utterly confused when my prospective employers asked: “What type?” I looked blankly at the panel of experts while stuttering for an answer.

What the hell do they mean?

“Rugby or Soccer?”

“Oh, soccer.”

I felt a right dickhead which made me even more nervous. Then, when asked what the Doppler effect was, I answered something like ‘a train gets noisy as it gets closer and a bit quieter when it goes away.’

Not my finest hour and unsurprisingly, I didn’t get the job.

It brought it all back and I talked to the young shop assistant for ages about my life-long fascination with being underwater while I explored his veritable treasure trove of a dive shop.

This was to be the beginning of my delayed love affair with our oceans.

That Christmas I opened my presents to discover a PADI open water dive course.

My wonderful partner Tracey had been listening and had not only bought the course for me but also one for herself.

I was so excited and after a few confined dives in a Luton swimming pool, we headed off to the island of Filetheyo in the Maldives to experience open water diving for the first time.

Just before we were about to leave, my Mum died.

Mum had been suffering from dementia for a few years and lived in a home near my sister in Kent. I’d visit her whenever I could but, near the end of her life, she wasn’t sure who I was anymore.

She thought I was her brother, Arthur.

“How you get here, Arthur?”

“By car Mum.”

“You can’t drive, you don’t have a licence.”

I did have a licence but my uncle didn’t.

It was sad to see her deteriorate so much towards the end and in a way, it was a blessed relief when she finally passed.

My Dad had died a few years before and as so often happens, Mum just faded away after that.

We delayed our trip for a few weeks to arrange and attend her funeral before finally heading off to Filetheyo.

I loved my Mum and the timing of her death only served to heighten what came next.

I’ll never forget my first dive.

So many things went through my head.

The reef.

Millions of fish.

The colours.

My Mum.

The life I’d had.

The life I didn’t have.

The trials, the tribulations, the rewards.

That dive was everything I dreamed of, and more.

After the dive Trace and I sat on a beautiful jetty watching the sunset.

We drank a toast to my mum.

It was really emotional but I had this strange feeling that I was about to start a new chapter.

Sport Aid was over and I was getting my life back together.

During the trip, we made some new friends. Bob McCusker – a Scot from Worthing and a BSAC diver – and Angela, his partner. Angela was also learning to dive and was on the same course as us. We all got on well and shared dinners, alcohol and our new dive experiences.

We are still friends to this day.

A couple of years after Filetheyo, we all went on another dive trip to Mexico.

We had been diving on Chinchorro Banks all day and were relaxing under a huge blanket of stars on the Yucatan peninsula. I loved stargazing at the best of times, but here there was zero light pollution and the sky was immense.

As we knocked back the best margaritas ever, I had another epiphany.

While I’d been f*****g around growing tomatoes and then trying to get the world to run, about 20 million people had taken up recreational scuba diving.

Every single one kept a log book.

If, like me, they recorded everything they saw then surely that data could be really useful?

Bob and I concluded that it must.

The assumption was mainly fuelled by tequila at the time, so I decided to check it out for sure when I got home.

I called someone at the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

UNEP is a UN agency and co-ordinates its environmental activities, assisting developing countries in implementing environmentally-sound policies and practices.

It seemed a good place to start.

They told me to get in touch with the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) and so I started to make travel plans again. WCMC sounded exotic and distant and I expected to find them based in Hawaii or Fiji or somewhere like that.

I found them in Cambridge.

I took a trip to their offices and met with senior marine biologists. I presented my idea of ‘citizen science’, collecting data from divers’ logs and giving our oceans a health check.

“Would the data be useful?”

“Very. If we could get divers to act like twitchers (another name for birdwatchers), the data could be really valuable.”

It was an amazing response and for the first time in a very, very long time, I started to get a little excited again. It seemed that life had gone around in a great big circle, that my destiny was diving from the start and my incorrect answer to my first interviewer’s question just threw me off at a tangent for 30 odd years!

Our oceans were the lungs of our planet and they were very unhealthy.

I knew that much.

Fish stocks were harvested well beyond their sustainable limits and climate change threatened rising sea levels, increased salinity and the loss of the beautiful coral reefs I had just been so privileged to see.

Citizen Science.

Could 20 million people become scientists, collect data and give our oceans the health check they needed?

Maybe.

Over the next year, I worked closely with UNEP and about 30 marine biologists around the world. We considered every inch of coastal water and broke it down into specific eco regions. Each biologist selected marine indicator species for each eco region.

When tallied, the species would tell us a considerable amount about each region and overall, the changing state of the world’s oceans.

I designed a website – earthdive.com – to provide an online platform for divers to share their logbooks and indicator species.

My dear friends Bob and Angela became involved and a great guy called Matt Lovell helped build the website for nothing. UNEP-WCMC became a partner and the website was launched.

We made a great team and I went on BBC News to tell the world about it.

I was so fucking nervous that day.

Anxious to lift up my head again.

But I did.

It had taken a long time but I was ready again.

I still wanted to change the world.

I believed I could and I would die trying.

Let’em kick me if they wanted.

UNEP executive director Klaus Toepfer said something supportive:

“The conservation of marine biodiversity is a vital issue of our age. By collecting valuable scientific data, Earthdive’s citizen scientists will actually take part in a massive global effort to monitor and help conserve life on this planet.”

I was on my way again and very soon, Earthdive attracted citizen scientists in more than 100 countries.

As my confidence came back I looked at other ways in which I could enhance and improve the programme. It soon became apparent that divers weren’t all like me and needed encouragement to share their dive logs.

Earthdive needed a lot of publicity for it to really work. It needed to make its citizen scientists important in much the same way Sport Aid made its 20 million runners the stars of the show.

We needed to take control of our world again.

We didn’t need scientists to do our work. We could collect data for them and take our findings to the policymakers of the world to demand action for our oceans.

I needed to get that message out.

I needed to tell the world that our oceans were the largest sink for anthropogenic carbon in the world and that we needed to protect them.

Bigger and more important than any rain forest.

I needed to tell them that an estimated 12.7 million tonnes of plastic – everything from plastic bottles and bags to microbeads – ended up in our oceans each year.

A truck load of rubbish every minute!

I needed to tell them that yes, sharks do kill a few people each year by accident but we kill 100 million of them each year, by design.

I needed to tell people everywhere that we were fucking things up big time and needed to change.

That’s when my soul rebooted again and I dreamed up Earthdive Explorer.

Earthdive Explorer would be an ocean-going research ship. My plan was to sail it on a global voyage of historic importance. Originally, it was to leave San Francisco on the 50th Anniversary of the United Nations and its departure was to form a major part of the UN celebrations.

The team aboard would consist of men and women of various nationalities, ages and backgrounds. All would be divers, marine scientists or filmmakers. Together, they would form the ocean-based element of the Earthdive project. Fully equipped with satellite communication technology, scuba and film recording equipment, Earthdive Explorer was designed to link to the world via television, radio and the unique land-based operation and website.

The ship was to travel from ocean to ocean, recording data, mobilising support, lobbying policymakers, diving with celebrities, meeting heads of state and creating extensive TV footage.

One year later, it was to return to the United Nations in New York to deliver specific recommendations for the preservation of our oceans, along with an international petition demanding action.

The TV programming included video news releases, news-feeds, long-run series, mini-series, blue-chip specials, documentaries, UN special event(s) and a special documentary of the voyage.

I set up an amazing collaboration with National Geographic and Granada TV.

Earthdive Explorer was to engage a whole new generation of global television viewers and empower them to make a difference to the world in which they lived.

Fantastic animals and underwater locations always hold an audience’s attention. But if we could add inspiring human stories about ordinary people who set out on a voyage to change the world – then I believed a huge global audience would be captivated and my citizen scientists would be inspired.

The Earthdive Explorer series would be visually stunning. On-board technology allowing filming as never before. All crew gear, down to the covers on dive tanks, designed specifically for the project. The TV series could be directed, shot and edited using the most innovative and imaginative techniques to be found across mainstream documentary and drama.

As well as two natural history and documentary crews, a specialist crew would film the lives and work of the crew’s scientists, biologists, divers and filmmakers.

The Earthdive Explorer series was designed to be family television that offered something for everybody. ROVs exploring shipwrecks or searching the ocean depths for mythical giant squid. Viewers experiencing the adrenaline rush of being buzzed by sharks as they ‘climbed’ down an underwater mountain, wondering at the breath-taking beauty of an ocean at night.

Watching celebrities nervously diving with great white sharks. An audience of citizen scientists helping to make decisions that affect the world they live in.

Its similarities with the best parts of Sport Aid were no accident.

For over a year I worked with Granada Television and an amazing guy, underwater cameraman Jeff Goodman, to develop major strands for the programme schedule. At the same time, I explored sponsorship.

Earthdive Explorer was going to be expensive but the combined reach of the National Geographic and ITV programme made the return on investment really doable for a blue-chip brand.

I started a dialogue with a few potential sponsors and very soon I was travelling the world again to seek support for another project.

Once again, using money I didn’t have.

Where I could, I’d combine my US trips with seeing John.

I’d sometimes stay with him and commute into Washington DC to meet National Geographic. They also had an operation in London and I was able to develop the main concept with them here.

Seeking and chasing down sponsorship took a long time but finally a serious dialogue started with British Petroleum (BP).

They seemed very interested.

Before long, I was working with their designated advertising and promotion agencies and we got closer and closer to the finer details of a partnership.

Weeks turned into months and before long a whole year had passed. ITV, Nat Geo, the agencies, me, we all committed a huge amount of time and resource and inched closer and closer to a final agreement.

Then something really terrible happened.

The Deepwater Horizon oil spill, also referred to as the BP oil spill was an industrial disaster. It began on April 20, 2010, in the Gulf of Mexico on the BP-operated Macondo Prospect.

Killing 11 people, it was the biggest marine oil spill in the history of the petroleum industry, estimated to be between eight and 31 per cent larger in volume than the previous record held by the Ixtoc I oil spill.

The US Government estimated the total discharge at 4.9 million barrels. It took nearly five months and several failed efforts before the well was finally sealed on September 19, 2010.

A massive response ensued to protect beaches, wetlands and estuaries utilising skimmer ships, floating booms, controlled burns and 1.84 million gallons of oil dispersant. Due to spill and adverse effects from the clean-up activities, extensive damage to marine and wildlife habitats was reported.

In Louisiana, 2,222 tonnes of oily material was removed from the beaches, more than double the amount collected in 2012. Oil clean-up crews worked four days a week on 55 miles of Louisiana shoreline.

Oil continued to be found as far from the Macondo site as the waters off the Florida Panhandle and Tampa Bay, where scientists said the oil and dispersant mixture was embedded in the sand.

It was reported that dolphins and other marine life continued to die in record numbers with infant dolphins dying at six times the normal rate.

It was a disaster in so many ways and was the death knell of the BP Earthdive Explorer.

A lot of physical and emotional energy in addition to money went into that project and I was forced to take a big step backwards and lick my wounds for a while.

Had it been 30 years ago, I would have battled on, single-mindedly, and might have found another sponsor.

I was nearly 60 and things were different.

I maintained a web-presence for Earthdive, a portal for news and information for the diving and marine conservation communities which I continue to run today.

I marvel at the Blue Planet and Blue Planet II programmes. The BBC series has given me much comfort that the concept of Earthdive Explorer was right and proper.

It highlighted the issue of ocean plastic throughout, with breathtaking, heartbreaking and brutally honest images of its impacts.

The footage of a sperm whale attempting to eat a discarded plastic bucket and a mother pilot whale carrying her dead calf for days outraged people.

It is images like this that galvanize public opinion and help effect change.

The footage was not typical of Blue Planet in that Sir David Attenborough and his production team tended to steer clear of conservation issues in the past, preferring instead to celebrate the natural world.

Blue Planet II was different.

It pinpointed these issues – head on.

Couple this with elements of Earthdive Explorer and so much could be achieved for ocean conservation and the future of our planet.

Maybe one day. . .

I Ran the World by Chris Long is available on Amazon Books here.

Visit www.earthdive.com to find out more!

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs

Creature Feature: Dusky Shark

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

This month we’re taking a look at the Dusky Shark, a highly migratory species with a particularly slow growth rate and late age at maturity.

Dusky sharks are one of the largest species within the Carcharhinus genus, generally measuring 3 metres total length but able to reach up to 4.2 metres. They are grey to grey-brown on their dorsal side and their fins usually have dusky margins, with the darkest tips on the caudal fin.

Dusky Sharks can often be confused with other species of the Carcharhinus genus, particularly the Galapagos Shark (Carcharhinus galapagensis). They have very similar external morphology, so it can be easier to ID to species level by taking location into account as the two species occupy very different ecological niches – Galapagos Sharks prefer offshore seamounts and islets, whilst duskies prefer continental margins.

Hybridisation:

A 2019 study found that Dusky Sharks are hybridising with Galapagos Sharks on the Eastern Tropical Pacific (Pazmiño et al., 2019). Hybridisation is when an animal breeds with an individual of another species to produce offspring (a hybrid). Hybrids are often infertile, but this study found that the hybrids were able to produce second generation hybrids!

Long distance swimmers:

Dusky sharks are highly mobile species, undertaking long migrations to stay in warm waters throughout the winter. In the Northern Hemisphere, they head towards the poles in the summer and return southwards towards the equator in winter. The longest distance recorded was 2000 nautical miles!

Very slow to mature and reproduce:

The Dusky Shark are both targeted and caught as bycatch globally. We already know that elasmobranchs are inherently slow reproducers which means that they are heavily impacted by overfishing; it takes them so long to recover that they cannot keep up with the rate at which they are being fished. Dusky Sharks are particularly slow to reproduce – females are only ready to start breeding at roughly 20 years old, their gestation periods can last up to 22 months, and they only give birth every two to three years. This makes duskies one of the most vulnerable of all shark species.

The Dusky Shark is now listed on Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species (CMS), but further action is required to protect this important species.

Scientific Name: Carcharhinus obscurus

Family: Carcharhinidae

Maximum Size: 420cm (Total Length)

Diet: Bony fishes, cephalopods, can also eat crustaceans, and small sharks, skates and rays

Distribution: Patchy distribution in tropical and warm temperate seas; Atlantic, Indo-Pacific and Mediterranean.

Habitat: Ranges from inshore waters out to the edge of the continental shelf.

Conservation status: Endangered.

For more great shark information and conservation visit the Shark Trust Website

Images: Andy Murch

Diana A. Pazmiño, Lynne van Herderden, Colin A. Simpfendorfer, Claudia Junge, Stephen C. Donnellan, E. Mauricio Hoyos-Padilla, Clinton A.J. Duffy, Charlie Huveneers, Bronwyn M. Gillanders, Paul A. Butcher, Gregory E. Maes. (2019). Introgressive hybridisation between two widespread sharks in the east Pacific region, Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 136(119-127), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2019.04.013.

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs

Creature Feature: Undulate Ray

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

This month we’re looking at the Undulate Ray. Easily identified by its beautiful, ornate pattern, the Undulate Ray gets its name from the undulating patterns of lines and spots on its dorsal side.

This skate is usually found on sandy or muddy sea floors, down to about 200 m deep, although it is more commonly found shallower. They can grow up to 90 cm total length. Depending on the size of the individual, their diet can range from shrimps to crabs.

Although sometimes called the Undulate Ray, this is actually a species of skate, meaning that, as all true skates do, they lay eggs. The eggs are contained in keratin eggcases – the same material that our hair and nails are made up of! These eggcases are also commonly called mermaid’s purses and can be found washed up on beaches all around the UK. If you find one, be sure to take a picture and upload your find to the Great Eggcase Hunt – the Shark Trust’s flagship citizen science project.

It is worth noting that on the south coasts, these eggcases can be confused with those of the Spotted Ray, especially as they look very similar and the ranges overlap, so we sometimes informally refer to them as ‘Spundulates’.

Scientific Name: Raja undulata

Family: Rajidae

Maximum Size: 90cm (total length)

Diet: shrimps and crabs

Distribution: found around the eastern Atlantic and in the Mediterranean Sea.

Habitat: shelf waters down to 200m deep.

Conservation Status : As a commercially exploited species, the Undulate Ray is a recovering species in some areas. The good thing is that they have some of the most comprehensive management measures of almost any elasmobranch species, with both minimum and maximum landing sizes as well as a closed season. Additionally, targeting is entirely prohibited in some areas. They are also often caught as bycatch in various fisheries – in some areas they can be landed whilst in others they must be discarded.

IUCN Red List Status: Endangered

For more great shark information and conservation visit the Shark Trust Website

Image Credits: Banner – Sheila Openshaw; Illustration – Marc Dando

-

News3 months ago

News3 months agoHone your underwater photography skills with Alphamarine Photography at Red Sea Diving Safari in March

-

News3 months ago

News3 months agoCapturing Critters in Lembeh Underwater Photography Workshop 2024: Event Roundup

-

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs3 months ago

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs3 months agoCreature Feature: Swell Sharks

-

Blogs2 months ago

Blogs2 months agoMurex Resorts: Passport to Paradise!

-

Blogs2 months ago

Blogs2 months agoDiver Discovering Whale Skeletons Beneath Ice Judged World’s Best Underwater Photograph

-

Gear Reviews2 weeks ago

Gear Reviews2 weeks agoGEAR REVIEW – Revolutionising Diving Comfort: The Sharkskin T2 Chillproof Suit

-

Gear Reviews3 months ago

Gear Reviews3 months agoGear Review: Oceanic+ Dive Housing for iPhone

-

Marine Life & Conservation2 months ago

Marine Life & Conservation2 months agoSave the Manatee Club launches brand new webcams at Silver Springs State Park, Florida