Marine Life & Conservation Blogs

Bluefin Tuna Back in UK Waters

Bluefin Tuna are back in the seas around the UK after decades of decline and absence. It has been proposed this could be due to warming seas rather than species recovery. After generations of overfishing, pollution and lack of food, it is astonishing how resilient these Tuna and other species are in their survival and wondrous that they should be able to return at all. What is not so wondrous is human nature. The Angling Trust are now petitioning for the protection status for these fish to be changed to establish a catch and release licensed fishery in what seems to me to be a case of self gratification and financial profit over sensible environmental concern.

New research by Dr Robin Faillettaz from the University of Lille (France), his French co-workers Drs Gregory Beaugrand and Eric Goberville, and Dr Richard Kirby from the UK – as part of the scientific programme CLIMIBIO (www.climibio.univ-lille.fr/) – has revealed that warmer seas can explain the reappearance of tuna around the UK.

Dr Richard Kirby says “Bluefin tuna have been extensively overfished during the 20th century and the stock was close to its lowest in 1990, a fact that further indicates the recent changes in distribution are most likely environmentally driven rather than due to fisheries management and stock recovery. Before we further exploit bluefin tuna either commercially or recreationally for sport fishing, we should consider whether it would be better to protect them by making the UK’s seas a safe space for one of the ocean’s most endangered top fish.”

I asked him for more information and he sent me the following report:

“Bluefin tuna are back in the sea around the UK after decades of absence and a new study says that warming seas can explain why. Bluefin tuna are one of the biggest, most valuable, most sought after, and most endangered fish in the oceans. Sport fishermen excited at the prospect of catching a fish that can grow to over 900kg have already launched a UK campaign to allow recreational fishing for one of game fishing’s top targets. But should we catch and exploit this endangered species or should we make UK waters a safe space for this incredible fish? Important questions to answer are why has this endangered fish suddenly returned to the UK after an absence of nearly 40 years and are bluefin tuna now more abundant or have they just changed in their distribution?

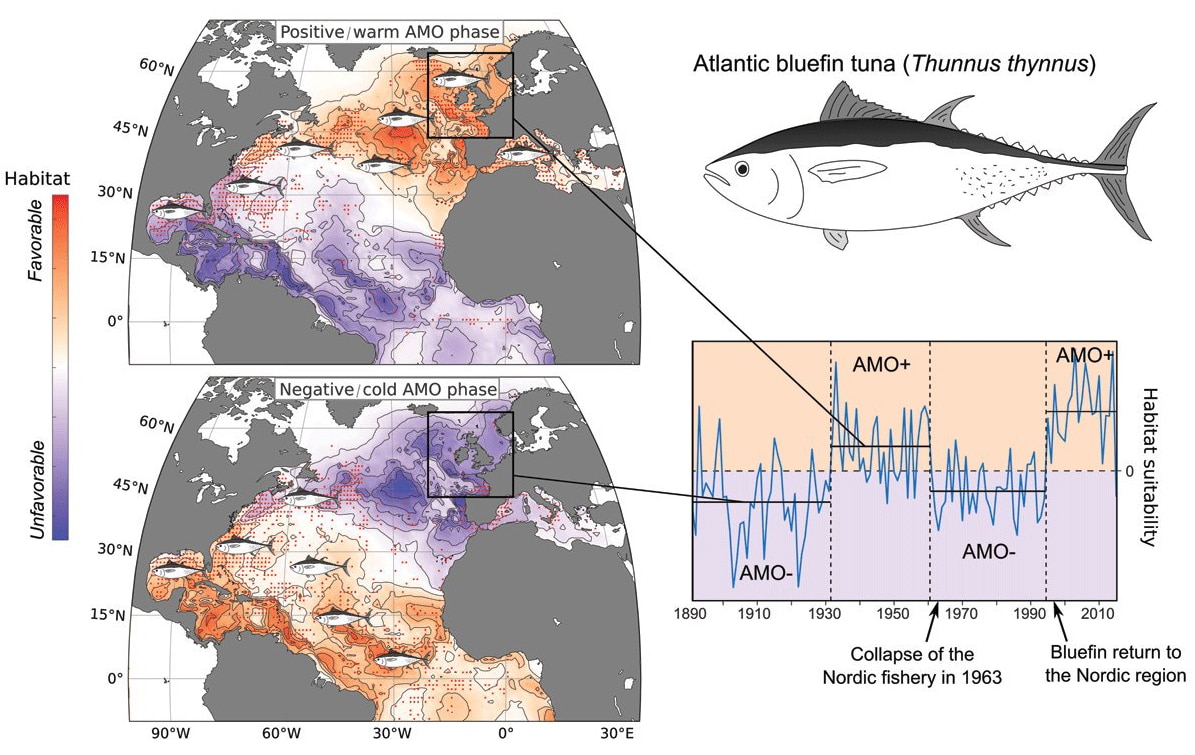

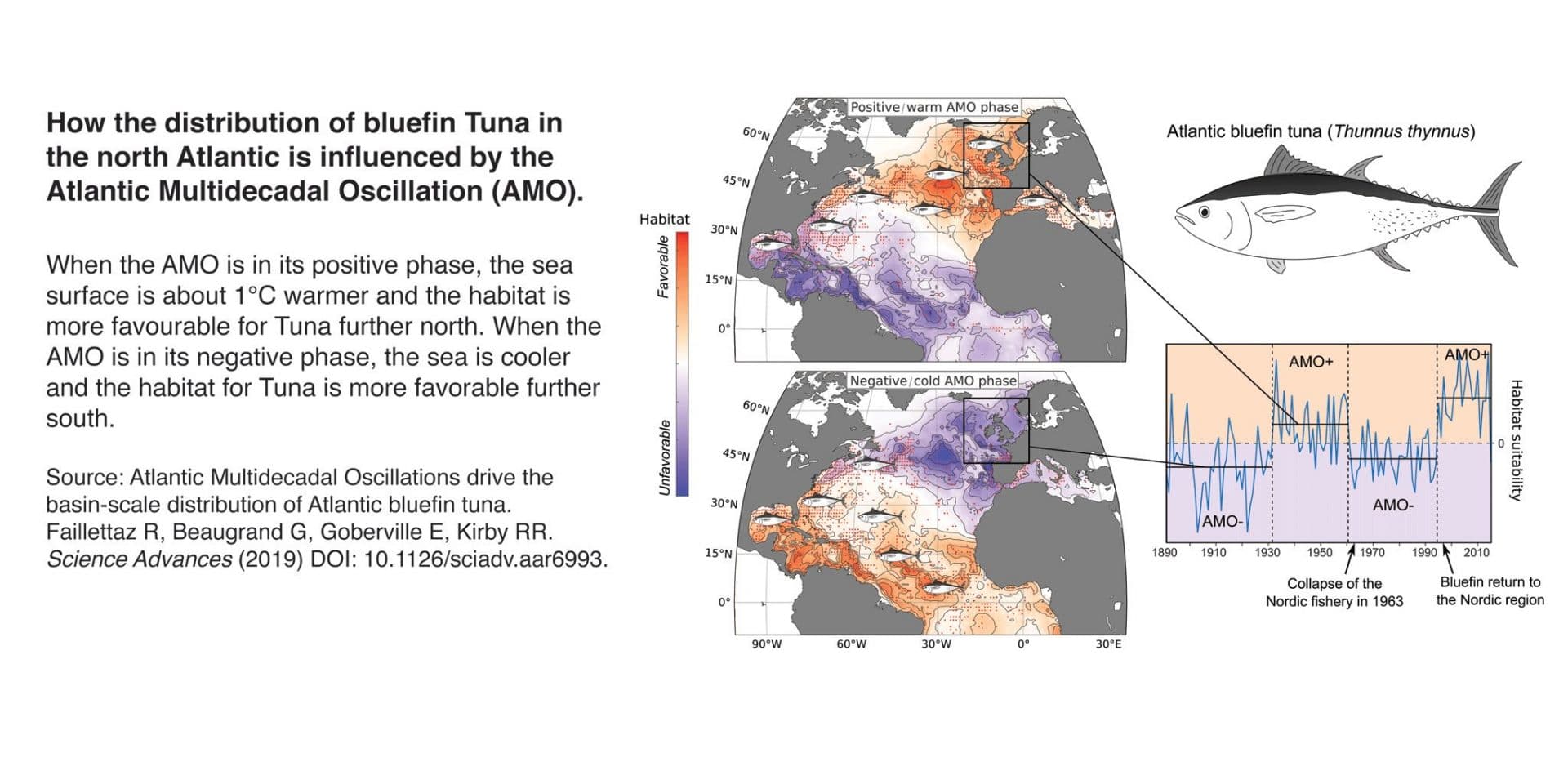

CLIMIBIO’s research shows that the disappearance and reappearance of bluefin tuna in European waters can be explained by hydroclimatic variability due to the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO), a northern hemisphere climatic oscillation that increases the sea temperature when in its positive phase like it is now.

To come to their conclusion, the scientists examined the changing abundance and distribution of bluefin tuna in the Atlantic Ocean over the last 200 years. They combined two modelling approaches, focusing on the intensity of the catches over time and on the distribution of the fish’s occurrence, i.e. when it was observed or caught. Their results are unequivocal: the AMO is the major driver influencing both the abundance and the distribution of the bluefin tuna.

The Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation affects complex atmospheric and oceanographic processes in the northern hemisphere including the strength and direction of ocean currents, drought on land, and even the frequency and intensity of Atlantic hurricanes. Approximately every 60 to 120 years the AMO switches between positive and negative phases to create a basin-scale shift in the distribution of Atlantic bluefin tuna. During a warm AMO phase, such as since the mid-1990s, bluefin tuna forage as far north as Greenland, Iceland and Norway and almost disappear from the central and south Atlantic. During its previous warm phase – at the middle of the 20th century – the North Sea had a bluefin tuna fishery that rivalled the Mediterranean and the Bluefin Tunny sportfishing club – known worldwide – was founded in Scarborough. However, during a cold AMO phase, such as that between 1963-1995, bluefin tuna move south and are more frequently found in the western, central, and even southern Atlantic, with few fish caught above 45°N. Dr Faillettaz says that “The ecological effects of the AMO have long been overlooked and our results represent a breakthrough in understanding the history of bluefin tuna in the North Atlantic.”

In fact, the most striking example of the effect of the AMO on bluefin tuna is the sudden collapse of the large Nordic bluefin tuna fishery in 1963. The collapse coincides perfectly with the most rapid known switch in the AMO from its highest to its lowest recorded value in only two years. After that switch tuna also vacated the North Sea, and the conditions remained unfavourable for bluefin tuna in the northern Atlantic until the late 1990s when it started to reappear around the UK.

The scientists expect that bluefin tuna will continue to migrate to the UK and North Sea waters every year until the AMO reverses to a cold phase. However, they also highlight that the additional effect of global warming on sea temperatures will make the future response of bluefin tuna to changes in the AMO uncertain. Further to the effect of the AMO on where and when bluefin tuna occur in the Atlantic, the study also found that this climatic oscillation influences their recruitment, i.e., how many juvenile bluefin tuna grow to become adults.

Dr Faillettaz said that “when water temperature increases during a positive AMO, bluefin tuna move further north. However, the most positive phases of the AMO also have a detrimental effect upon recruitment in the Mediterranean Sea, which is currently the most important spawning ground, and that will affect adult abundance a few years later. If the AMO stays in a highly positive phase for several years, we may encounter more bluefin tuna in our waters, but the overall population could actually be decreasing.”

Consequently, Dr Beaugrand warns that “global warming superimposed upon the AMO is likely to alter the now familiar patterns we have seen in bluefin tuna over the last four centuries. Increasing global temperatures may cause Atlantic bluefin tuna to persist in the Nordic region and shrink the species distribution in the Atlantic Ocean, and it may even cause the fish to disappear from the Mediterranean Sea, which is currently the most important fishery.”

Dr Goberville also raises another important observation saying that “because bluefin tuna are so noticeable, they are also an indicator of current temperature driven changes in our seas that are occurring throughout the marine food chain, from the plankton to fish and seabirds”.

The Atlantic bluefin tuna fishery indeed encompasses most of the problems seen in fisheries around the world, including fleet overcapacity and political mismanagement; the species’ distribution crosses exclusive economic zones and spans international, open-access waters (i.e. the entire North Atlantic, from the Mediterranean Sea to the Gulf of Mexico). Added to that, the long-term fluctuation in Atlantic bluefin tuna abundance was hitherto understood poorly, which represents a fundamental gap in this fish’s sustainable management.

Dr Kirby says that “we have shown why bluefin tuna occur when and where in the North Atlantic and what may influence their recruitment and abundance, and this is fundamental to understanding the management of a fish that is endangered due to overfishing. Bluefin tuna have been extensively overfished during the 20th century and the stock was close to its lowest in 1990, a fact that further indicates the recent changes in distribution are most likely environmentally driven rather than due to fisheries management and stock recovery.”

Before we further exploit bluefin tuna either commercially or recreationally for sport fishing, we should consider whether it would be better to protect them by making the UK’s seas a safe space for one of the ocean’s most endangered top fish.”

The lead author Dr Faillettaz concludes: “Our results demonstrate that local changes in Atlantic bluefin tuna abundance can reflect large-scale shifts in a species’ distribution that are unrelated to improvements or worsening of a stock’s abundance. In this context we hope that our study will highlight the need to consider the environment when planning the sustainable management of all migratory fish species.”

For further information

Dr Richard Kirby

E-mail: Richard.Kirby@planktonpundit.org

Dr Robin Faillettaz

E-mail: Robin.Faillettaz@univ-lille1.fr

For further reading

Could big-game fishing return to the UK?

Warming Seas linked to bluefin tuna surge in UK waters

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs

Creature Feature: Dusky Shark

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

This month we’re taking a look at the Dusky Shark, a highly migratory species with a particularly slow growth rate and late age at maturity.

Dusky sharks are one of the largest species within the Carcharhinus genus, generally measuring 3 metres total length but able to reach up to 4.2 metres. They are grey to grey-brown on their dorsal side and their fins usually have dusky margins, with the darkest tips on the caudal fin.

Dusky Sharks can often be confused with other species of the Carcharhinus genus, particularly the Galapagos Shark (Carcharhinus galapagensis). They have very similar external morphology, so it can be easier to ID to species level by taking location into account as the two species occupy very different ecological niches – Galapagos Sharks prefer offshore seamounts and islets, whilst duskies prefer continental margins.

Hybridisation:

A 2019 study found that Dusky Sharks are hybridising with Galapagos Sharks on the Eastern Tropical Pacific (Pazmiño et al., 2019). Hybridisation is when an animal breeds with an individual of another species to produce offspring (a hybrid). Hybrids are often infertile, but this study found that the hybrids were able to produce second generation hybrids!

Long distance swimmers:

Dusky sharks are highly mobile species, undertaking long migrations to stay in warm waters throughout the winter. In the Northern Hemisphere, they head towards the poles in the summer and return southwards towards the equator in winter. The longest distance recorded was 2000 nautical miles!

Very slow to mature and reproduce:

The Dusky Shark are both targeted and caught as bycatch globally. We already know that elasmobranchs are inherently slow reproducers which means that they are heavily impacted by overfishing; it takes them so long to recover that they cannot keep up with the rate at which they are being fished. Dusky Sharks are particularly slow to reproduce – females are only ready to start breeding at roughly 20 years old, their gestation periods can last up to 22 months, and they only give birth every two to three years. This makes duskies one of the most vulnerable of all shark species.

The Dusky Shark is now listed on Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species (CMS), but further action is required to protect this important species.

Scientific Name: Carcharhinus obscurus

Family: Carcharhinidae

Maximum Size: 420cm (Total Length)

Diet: Bony fishes, cephalopods, can also eat crustaceans, and small sharks, skates and rays

Distribution: Patchy distribution in tropical and warm temperate seas; Atlantic, Indo-Pacific and Mediterranean.

Habitat: Ranges from inshore waters out to the edge of the continental shelf.

Conservation status: Endangered.

For more great shark information and conservation visit the Shark Trust Website

Images: Andy Murch

Diana A. Pazmiño, Lynne van Herderden, Colin A. Simpfendorfer, Claudia Junge, Stephen C. Donnellan, E. Mauricio Hoyos-Padilla, Clinton A.J. Duffy, Charlie Huveneers, Bronwyn M. Gillanders, Paul A. Butcher, Gregory E. Maes. (2019). Introgressive hybridisation between two widespread sharks in the east Pacific region, Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 136(119-127), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2019.04.013.

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs

Creature Feature: Undulate Ray

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

This month we’re looking at the Undulate Ray. Easily identified by its beautiful, ornate pattern, the Undulate Ray gets its name from the undulating patterns of lines and spots on its dorsal side.

This skate is usually found on sandy or muddy sea floors, down to about 200 m deep, although it is more commonly found shallower. They can grow up to 90 cm total length. Depending on the size of the individual, their diet can range from shrimps to crabs.

Although sometimes called the Undulate Ray, this is actually a species of skate, meaning that, as all true skates do, they lay eggs. The eggs are contained in keratin eggcases – the same material that our hair and nails are made up of! These eggcases are also commonly called mermaid’s purses and can be found washed up on beaches all around the UK. If you find one, be sure to take a picture and upload your find to the Great Eggcase Hunt – the Shark Trust’s flagship citizen science project.

It is worth noting that on the south coasts, these eggcases can be confused with those of the Spotted Ray, especially as they look very similar and the ranges overlap, so we sometimes informally refer to them as ‘Spundulates’.

Scientific Name: Raja undulata

Family: Rajidae

Maximum Size: 90cm (total length)

Diet: shrimps and crabs

Distribution: found around the eastern Atlantic and in the Mediterranean Sea.

Habitat: shelf waters down to 200m deep.

Conservation Status : As a commercially exploited species, the Undulate Ray is a recovering species in some areas. The good thing is that they have some of the most comprehensive management measures of almost any elasmobranch species, with both minimum and maximum landing sizes as well as a closed season. Additionally, targeting is entirely prohibited in some areas. They are also often caught as bycatch in various fisheries – in some areas they can be landed whilst in others they must be discarded.

IUCN Red List Status: Endangered

For more great shark information and conservation visit the Shark Trust Website

Image Credits: Banner – Sheila Openshaw; Illustration – Marc Dando

-

News3 months ago

News3 months agoHone your underwater photography skills with Alphamarine Photography at Red Sea Diving Safari in March

-

News3 months ago

News3 months agoCapturing Critters in Lembeh Underwater Photography Workshop 2024: Event Roundup

-

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs3 months ago

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs3 months agoCreature Feature: Swell Sharks

-

Blogs2 months ago

Blogs2 months agoMurex Resorts: Passport to Paradise!

-

Blogs2 months ago

Blogs2 months agoDiver Discovering Whale Skeletons Beneath Ice Judged World’s Best Underwater Photograph

-

Gear Reviews2 weeks ago

Gear Reviews2 weeks agoGEAR REVIEW – Revolutionising Diving Comfort: The Sharkskin T2 Chillproof Suit

-

Marine Life & Conservation2 months ago

Marine Life & Conservation2 months agoSave the Manatee Club launches brand new webcams at Silver Springs State Park, Florida

-

Gear Reviews3 months ago

Gear Reviews3 months agoGear Review: Oceanic+ Dive Housing for iPhone