Marine Life & Conservation Blogs

The Sergeant Major Fish: Underdog to Super-Dad

You’re on a dive, minding your own business when suddenly, your mask is being bombarded by a frantic and extremely angry creature. In shock you reverse, exiting the firing line when you realise that the monster in question is none other than the Sergeant Major Fish.

If your biggest fear in the ocean is the ‘dreaded shark’, think again, it’s the Sergeant Major you really have to worry about!! In disbelief you take a second glance and notice that the creatures you once thought were small and peaceful are all behaving in this manner to anything crossing or invading their path.

Why do they behave like this? And why have you never noticed this before?

Background Check

Abudefduf is from the Arabic; abu “the one with”, def “side”, and duf “prominent”. Its name, referring to the vertical black bars on its side, roughly translating to “the one with prominent sides”. This is also where its gets its common name “Sergeant Major,” as the stripes resemble the bars on a military uniform. Despite the general common name Sergeant Major there are up to 20 species of this damselfish, part of the family Pomacentridae, that you can be found worldwide. Generally, their bodies are deep, oval and compressed with a continuous dorsal fin and a forked caudal fin, but each species varies in size and the number of dorsal fins, dorsal soft rays, anal spines and anal soft rays.

Meet the Locals

Here in the UAE we have the Indo-pacific Sergeant Abudefduf vaigiensis. Widely distributed throughout the Indo-Pacific: Red Sea, Indian Ocean to eastern Africa, north to southern Japan, and south to Australia. In 1991, it was even discovered in the Hawaiian Islands, possibly floating marine debris such as abandoned fishing nets, where it now coexists with the Hawaiian Sergeant Abudefduf abdominalis. They form large aggregations while feeding during the day and play hide and seek by themselves at night on coral reefs, tidal pools and rocky reefs at depths between 1 to 15 m. The Indo-pacific Sergeant can grow up to 20 centimetres long, feeding on zooplankton, benthic algae and small invertebrates.

The Interesting Part!

So now you have the Sergeant Major’s background check. Here’s the fascinating part!

Between March and August, the Sergeant Majors congregate in large numbers to reproduce. To start the process, the males prepare temporary nesting sites by coating patches of rocks, shipwrecks and corals with an adhesive substrate. The females then wander around looking for that special partner to mate with. When a female is near, the male will try to attract the female by preforming a unique and intriguing dance which involves moving up and down erratically, like the local dance club. If she’s digging his moves she will deposit up to 20,000 eggs. Once the eggs have dispersed, they attach themselves to the substrate the males prepared and will then be fertilized.

After all the fun, the females eventually take off leaving the males with all the responsibility of protecting his little patch. The male is extremely attentive by continuously aerating his eggs stopping fungus build up. He will also turn a darker bluish colour which most likely acts as a warning colour to predators or even possible camouflage. Any fish that comes too close are aggressively chased away and divers are left in bewilderment.

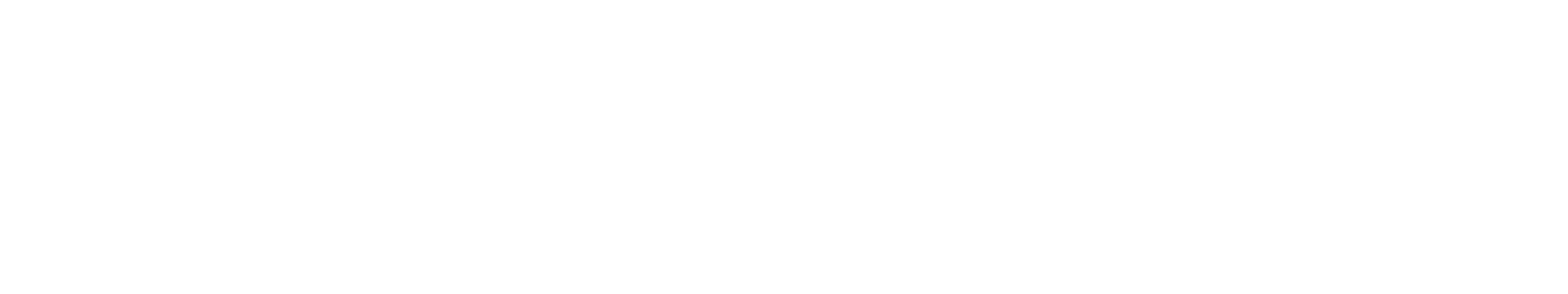

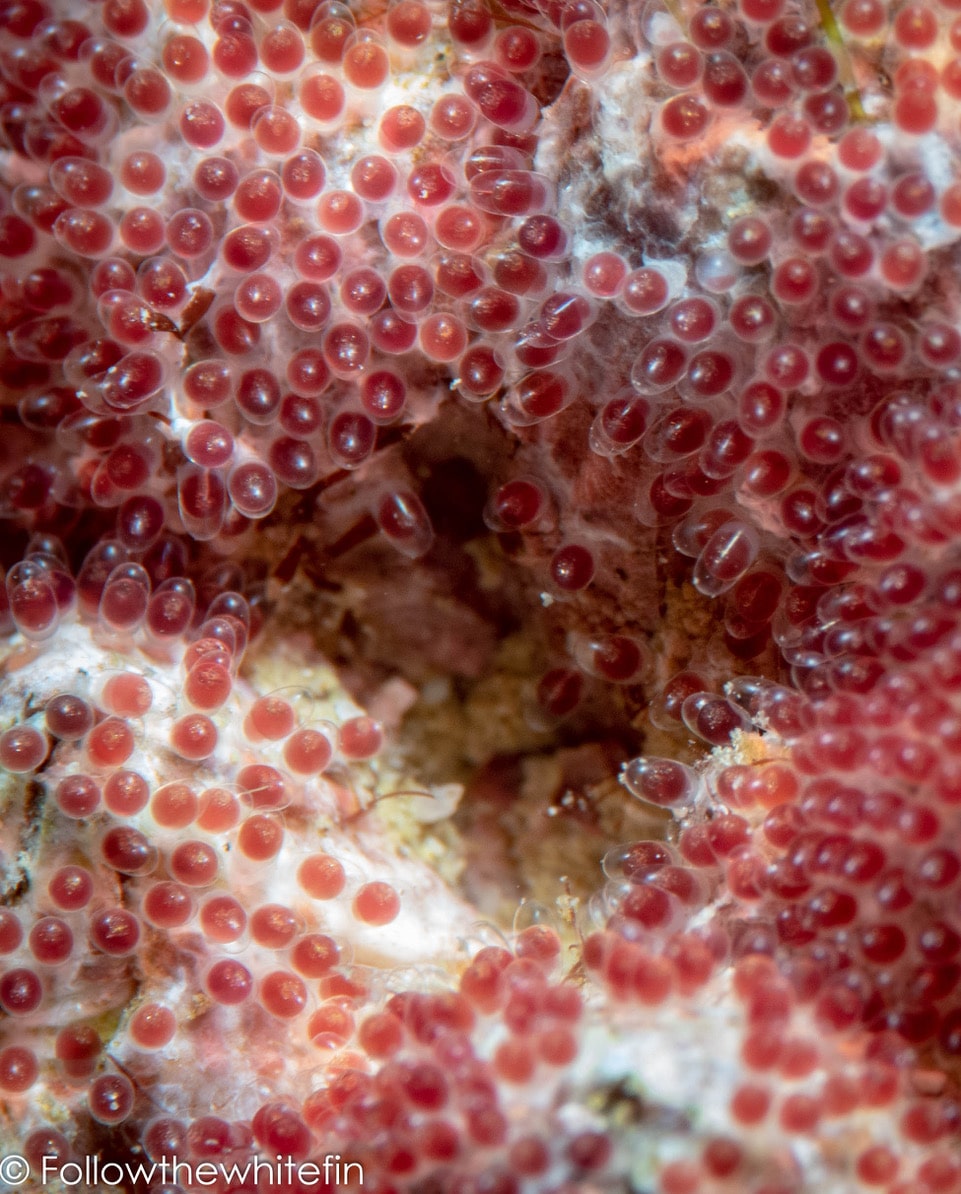

The eggs start as solid red ovals around 0.5-0.9mm. Once they are fertilised they start to turn a green colour with a deep red yolk leaving the surfaces as a patchwork. After 4-5 days the eggs will hatch an hour after sunset. If you are able to see the hatching, it can be amazing to watching as they wiggle out from the substrate and break free. Once hatched they are around 2.4mm in size and set off to tackle the big blue ocean.

I have been very privileged over the last few weeks to witness parts of this process and they are amazing to watch. The reef has literally been covered in patches of varying shades of red and green. The determination of the male Sergeant Major whilst hilarious to watch is also impressing for such a small creature to display. With my new camera I was able to catch some of these processes, but my next goal is to capture the courtship ritual and hatching (I may need a bigger camera though).

Next time you are out diving, make sure you don’t overlook the little guys, and look out for the patchwork of the ocean created by the Sergeant Major Fish.

Find out more about Kayleigh at www.followthewhitefin.com

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs

Creature Feature: Dusky Shark

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

This month we’re taking a look at the Dusky Shark, a highly migratory species with a particularly slow growth rate and late age at maturity.

Dusky sharks are one of the largest species within the Carcharhinus genus, generally measuring 3 metres total length but able to reach up to 4.2 metres. They are grey to grey-brown on their dorsal side and their fins usually have dusky margins, with the darkest tips on the caudal fin.

Dusky Sharks can often be confused with other species of the Carcharhinus genus, particularly the Galapagos Shark (Carcharhinus galapagensis). They have very similar external morphology, so it can be easier to ID to species level by taking location into account as the two species occupy very different ecological niches – Galapagos Sharks prefer offshore seamounts and islets, whilst duskies prefer continental margins.

Hybridisation:

A 2019 study found that Dusky Sharks are hybridising with Galapagos Sharks on the Eastern Tropical Pacific (Pazmiño et al., 2019). Hybridisation is when an animal breeds with an individual of another species to produce offspring (a hybrid). Hybrids are often infertile, but this study found that the hybrids were able to produce second generation hybrids!

Long distance swimmers:

Dusky sharks are highly mobile species, undertaking long migrations to stay in warm waters throughout the winter. In the Northern Hemisphere, they head towards the poles in the summer and return southwards towards the equator in winter. The longest distance recorded was 2000 nautical miles!

Very slow to mature and reproduce:

The Dusky Shark are both targeted and caught as bycatch globally. We already know that elasmobranchs are inherently slow reproducers which means that they are heavily impacted by overfishing; it takes them so long to recover that they cannot keep up with the rate at which they are being fished. Dusky Sharks are particularly slow to reproduce – females are only ready to start breeding at roughly 20 years old, their gestation periods can last up to 22 months, and they only give birth every two to three years. This makes duskies one of the most vulnerable of all shark species.

The Dusky Shark is now listed on Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species (CMS), but further action is required to protect this important species.

Scientific Name: Carcharhinus obscurus

Family: Carcharhinidae

Maximum Size: 420cm (Total Length)

Diet: Bony fishes, cephalopods, can also eat crustaceans, and small sharks, skates and rays

Distribution: Patchy distribution in tropical and warm temperate seas; Atlantic, Indo-Pacific and Mediterranean.

Habitat: Ranges from inshore waters out to the edge of the continental shelf.

Conservation status: Endangered.

For more great shark information and conservation visit the Shark Trust Website

Images: Andy Murch

Diana A. Pazmiño, Lynne van Herderden, Colin A. Simpfendorfer, Claudia Junge, Stephen C. Donnellan, E. Mauricio Hoyos-Padilla, Clinton A.J. Duffy, Charlie Huveneers, Bronwyn M. Gillanders, Paul A. Butcher, Gregory E. Maes. (2019). Introgressive hybridisation between two widespread sharks in the east Pacific region, Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 136(119-127), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2019.04.013.

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs

Creature Feature: Undulate Ray

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

This month we’re looking at the Undulate Ray. Easily identified by its beautiful, ornate pattern, the Undulate Ray gets its name from the undulating patterns of lines and spots on its dorsal side.

This skate is usually found on sandy or muddy sea floors, down to about 200 m deep, although it is more commonly found shallower. They can grow up to 90 cm total length. Depending on the size of the individual, their diet can range from shrimps to crabs.

Although sometimes called the Undulate Ray, this is actually a species of skate, meaning that, as all true skates do, they lay eggs. The eggs are contained in keratin eggcases – the same material that our hair and nails are made up of! These eggcases are also commonly called mermaid’s purses and can be found washed up on beaches all around the UK. If you find one, be sure to take a picture and upload your find to the Great Eggcase Hunt – the Shark Trust’s flagship citizen science project.

It is worth noting that on the south coasts, these eggcases can be confused with those of the Spotted Ray, especially as they look very similar and the ranges overlap, so we sometimes informally refer to them as ‘Spundulates’.

Scientific Name: Raja undulata

Family: Rajidae

Maximum Size: 90cm (total length)

Diet: shrimps and crabs

Distribution: found around the eastern Atlantic and in the Mediterranean Sea.

Habitat: shelf waters down to 200m deep.

Conservation Status : As a commercially exploited species, the Undulate Ray is a recovering species in some areas. The good thing is that they have some of the most comprehensive management measures of almost any elasmobranch species, with both minimum and maximum landing sizes as well as a closed season. Additionally, targeting is entirely prohibited in some areas. They are also often caught as bycatch in various fisheries – in some areas they can be landed whilst in others they must be discarded.

IUCN Red List Status: Endangered

For more great shark information and conservation visit the Shark Trust Website

Image Credits: Banner – Sheila Openshaw; Illustration – Marc Dando

-

News3 months ago

News3 months agoHone your underwater photography skills with Alphamarine Photography at Red Sea Diving Safari in March

-

News3 months ago

News3 months agoCapturing Critters in Lembeh Underwater Photography Workshop 2024: Event Roundup

-

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs3 months ago

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs3 months agoCreature Feature: Swell Sharks

-

Blogs2 months ago

Blogs2 months agoMurex Resorts: Passport to Paradise!

-

Blogs2 months ago

Blogs2 months agoDiver Discovering Whale Skeletons Beneath Ice Judged World’s Best Underwater Photograph

-

Gear Reviews2 weeks ago

Gear Reviews2 weeks agoGEAR REVIEW – Revolutionising Diving Comfort: The Sharkskin T2 Chillproof Suit

-

Marine Life & Conservation2 months ago

Marine Life & Conservation2 months agoSave the Manatee Club launches brand new webcams at Silver Springs State Park, Florida

-

Gear Reviews3 months ago

Gear Reviews3 months agoGear Review: Oceanic+ Dive Housing for iPhone