Marine Life & Conservation Blogs

Shark Baiting – Right or Wrong?

We’ve recently returned from an incredible trip diving the waters of Truk Lagoon. Undoubtedly a wreck heaven, where unexpectedly we also got the chance to take part in a baited shark dive on the outer reef of the lagoon. Black tips and grey reef sharks by the dozen turned up for the feeding frenzy, with a special appearance from a rather large silver tip who (literally) stole the show at the end. This was our first ever baited dive with sharks and got me thinking about shark dives in general and the practice of baiting.

There’s no doubt about it – a live shark is a billion times better than a dead shark. Without them, the marine ecosystem would collapse and coral reefs would slowly die off which would be an absolute travesty for the human race. While coral reefs only cover 0.0025 percent of the ocean floor, they generate half of Earth’s oxygen and absorb nearly one-third of the carbon dioxide generated from burning fossil fuels.

A report by the United Nation’s FAO (Food and Agriculture Organisation) shows that coral reefs are responsible for producing 17% of all globally consumed protein, with that ratio being 70% or greater in island and coastal countries like those of Micronesia. By May 2017, Earth had lost nearly half of its coral, and oceanic warming only continues to accelerate (Maybe this is grounds for a future article – let’s get back to the sharks…)

Any shark lover out there will be able to tell you the well-known stats that over 100 million sharks are killed each year (an incredible 11,500 per hour!), mainly for their fins or through by-catch. We also know that approx 10 people are killed each year by sharks worldwide – to put this into context, around 2,900 people are killed each year by the glorious Hippopotamus. There is far more exposure to the plight of sharks these days than ever before, and in recent years the battle against shark finning for the shark-fin soup trade has received a much higher profile. Has the tide turned? Will we see a decrease in the murder of these mighty pelagic creatures? Who knows, but anything to reduce the slaughter is a good thing.

For me, the drive to educate fishermen to realise that a shark fin from a dead shark is a one time payout, while live sharks can make repeat paydays through tourism and scuba diving must become more prevalent – but how do you ensure the paying punters lined up with their camera get the shot they dream of? Easy – you chum the water, and bait the sharks of course!

Now, this I’m sure is seen as a very contentious issue with camps on either side when it comes to the morals of this practice. I will do my best to see this from both sides. Of the approx. 10 deaths from shark attacks each year, I’m not aware of any of these deaths taking place through the practice of baiting sharks. Maybe because the processes in place are super stringent, but I don’t have any figures to hand to say either way.

What are the Cons? Why shouldn’t we bait sharks?

Some could argue that a healthy reef provides enough food for the entire ecosystem in place. Don’t mess with Mother Nature by encouraging sharks to behave in a way that is unnatural, as distracting sharks from their natural food source and behaviours has an adverse effect on fish numbers.

Another way to think it is that we are essentially training sharks to respond to food – human interaction then becomes associated with free food. We saw this with our very own eyes when the sharks responded to the noise of the boat engines while we got into position – they were already heading towards the back of the boat before any chum had even appeared, just like the way you train a dog to respond to a ‘clicker’. This is shown in the above video at around 25 seconds into the film.

The baited dive itself was set close to the main reef where a pulley system was set up, dragging down a large frozen block of frozen fish remains as a large lift bag was inflated. Interestingly the sharks were seemingly waiting at the exact location the bait would land all jostling for the best location. Clearly it’s not just man’s best friend that can learn new tricks!

Sharks are apex predators and don’t typically share territory – being at the top of the food chain results in lower numbers than other animals in the ecosystem, so competition isn’t always welcome.

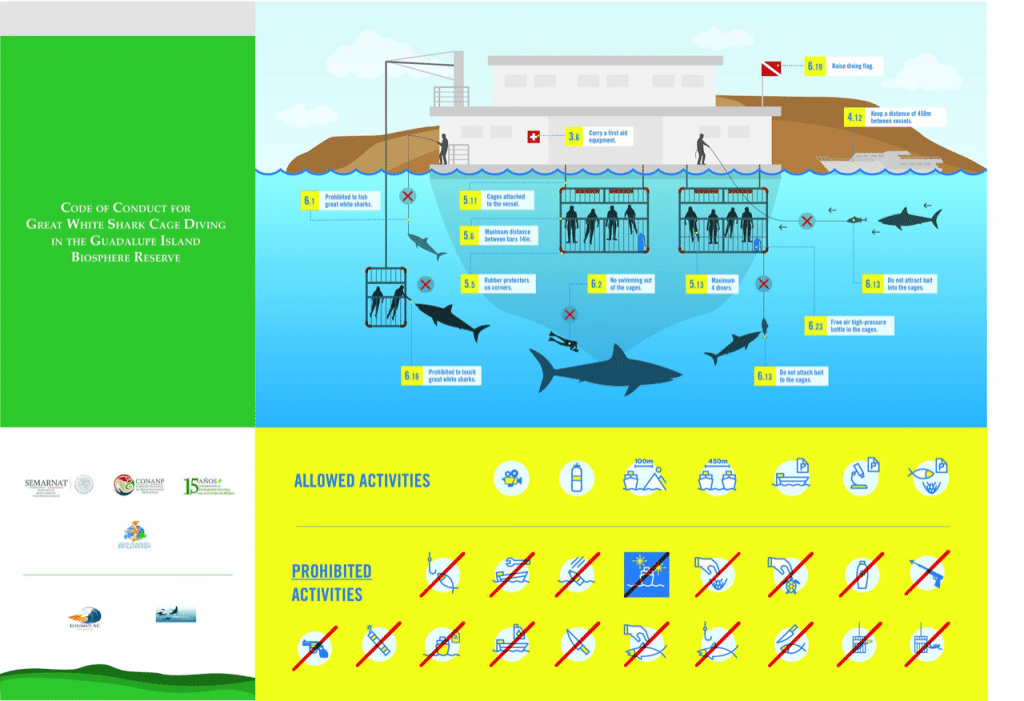

There is also the controversial practice of cage diving, predominantly with Great Whites – controversy hitting an all-time high in the waters of Guadalupe in October 2016 when a baited dive caused a charging Great White Shark to become trapped in the cage that the diver was in. The ensuing video footage of the incident saw the shark thrash around in a desperate attempt to free itself, in the end successful but certainly raised a few eyebrows! While chumming and baiting for sharks is legal, there are restrictions in place to promote protecting the safety of the sharks and divers sharing the water. It is assumed that the restricted practice of ‘shark wrangling’ was used in this event – the process of throwing in a severed Tuna head tied to a rope, and dragging it towards the cage as the shark approaches – as clearly shown in this image that was produced by the BIOSPHERE RESERVE OF GUADALUPE ISLAND, MEXICO – this practice is a no no.

What are the Pros? Why should we bait for sharks?

As a self-obsessed shark fanatic, I want to see them in their natural habit as often as possible, and as such I’ve been really lucky over the past few years to dive up close with a varied list including Bull, Thresher, Whale, Hammerhead, Silky, Oceanic White Tip, and a whole host of different coloured tip and reef sharks.

Some of the locations are famous for sightings, but even though you expect to see the sharks, there is no guarantee they will hang around for long and that at times can be the anxiety when spending large sums on an overseas trip.

I honestly hadn’t expected to see sharks in Truk – yes I know that Micronesia has a huge shark population, but I think I was so focused on what rust I would find that I discounted the trip of any significant marine life. I was totally fascinated by the whole set up. The professionalism of the briefing, the positioning of us, the divers, and the guides/crew in the water was perfect – even the equipment in place to bring the bait down into location so quickly. As a diver taking part on my first baited shark dive I was over the moon with what we saw – to see an apex predator tear apart a lump of meat a few metres in front of me was just fascinating, and at no time did I feel unsafe or at risk.

I’m going to raise my earlier point on the ongoing revenue a live shark can produce. You could argue that thousands of divers descending onto shark hot-spots has a real detrimental effect on the ocean/reef/sharks, however, I believe that tourism is key for so many developing countries and having the draw for scuba divers to visit faraway lands brings more to their economy than just the boat operators. The finning of sharks can’t continue the way it is, so I’m all for seeing baited shark dives taking precedent over these actions – far more people would benefit from this for sure.

Baiting for sharks also allows divers to actually see the sharks, and on many occasions allows studies to take place in a safe environment – I mean, the chances of diving with a Great White without a cage and non baited are fairly slim. Yeah, you could get lucky, but is it going to hang around – probably not, and that is why you bait the water and sit in a cage.

Undoubtedly, awareness and conservation efforts have increased over the past 20 odd years, and it has to be said that baited and cage dives with sharks around the world have done some good. There are now shark ambassadors around the world that are doing great things in educating people without out of date and misleading views that sharks are dangerous.

Having now taken part in our first baited dive with sharks, we would absolutely do it again – we were with a professional set up, where briefings were clear and safety paramount. Just do your homework before you set off.

Any opportunity that gives those with a love and passion for these great creatures the chance to see them up close, and in a safe environment, gets a massive tick from me!!

Richard and his partner Hayley run Black Manta Photography.

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs

Creature Feature: Dusky Shark

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

This month we’re taking a look at the Dusky Shark, a highly migratory species with a particularly slow growth rate and late age at maturity.

Dusky sharks are one of the largest species within the Carcharhinus genus, generally measuring 3 metres total length but able to reach up to 4.2 metres. They are grey to grey-brown on their dorsal side and their fins usually have dusky margins, with the darkest tips on the caudal fin.

Dusky Sharks can often be confused with other species of the Carcharhinus genus, particularly the Galapagos Shark (Carcharhinus galapagensis). They have very similar external morphology, so it can be easier to ID to species level by taking location into account as the two species occupy very different ecological niches – Galapagos Sharks prefer offshore seamounts and islets, whilst duskies prefer continental margins.

Hybridisation:

A 2019 study found that Dusky Sharks are hybridising with Galapagos Sharks on the Eastern Tropical Pacific (Pazmiño et al., 2019). Hybridisation is when an animal breeds with an individual of another species to produce offspring (a hybrid). Hybrids are often infertile, but this study found that the hybrids were able to produce second generation hybrids!

Long distance swimmers:

Dusky sharks are highly mobile species, undertaking long migrations to stay in warm waters throughout the winter. In the Northern Hemisphere, they head towards the poles in the summer and return southwards towards the equator in winter. The longest distance recorded was 2000 nautical miles!

Very slow to mature and reproduce:

The Dusky Shark are both targeted and caught as bycatch globally. We already know that elasmobranchs are inherently slow reproducers which means that they are heavily impacted by overfishing; it takes them so long to recover that they cannot keep up with the rate at which they are being fished. Dusky Sharks are particularly slow to reproduce – females are only ready to start breeding at roughly 20 years old, their gestation periods can last up to 22 months, and they only give birth every two to three years. This makes duskies one of the most vulnerable of all shark species.

The Dusky Shark is now listed on Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species (CMS), but further action is required to protect this important species.

Scientific Name: Carcharhinus obscurus

Family: Carcharhinidae

Maximum Size: 420cm (Total Length)

Diet: Bony fishes, cephalopods, can also eat crustaceans, and small sharks, skates and rays

Distribution: Patchy distribution in tropical and warm temperate seas; Atlantic, Indo-Pacific and Mediterranean.

Habitat: Ranges from inshore waters out to the edge of the continental shelf.

Conservation status: Endangered.

For more great shark information and conservation visit the Shark Trust Website

Images: Andy Murch

Diana A. Pazmiño, Lynne van Herderden, Colin A. Simpfendorfer, Claudia Junge, Stephen C. Donnellan, E. Mauricio Hoyos-Padilla, Clinton A.J. Duffy, Charlie Huveneers, Bronwyn M. Gillanders, Paul A. Butcher, Gregory E. Maes. (2019). Introgressive hybridisation between two widespread sharks in the east Pacific region, Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 136(119-127), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2019.04.013.

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs

Creature Feature: Undulate Ray

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

This month we’re looking at the Undulate Ray. Easily identified by its beautiful, ornate pattern, the Undulate Ray gets its name from the undulating patterns of lines and spots on its dorsal side.

This skate is usually found on sandy or muddy sea floors, down to about 200 m deep, although it is more commonly found shallower. They can grow up to 90 cm total length. Depending on the size of the individual, their diet can range from shrimps to crabs.

Although sometimes called the Undulate Ray, this is actually a species of skate, meaning that, as all true skates do, they lay eggs. The eggs are contained in keratin eggcases – the same material that our hair and nails are made up of! These eggcases are also commonly called mermaid’s purses and can be found washed up on beaches all around the UK. If you find one, be sure to take a picture and upload your find to the Great Eggcase Hunt – the Shark Trust’s flagship citizen science project.

It is worth noting that on the south coasts, these eggcases can be confused with those of the Spotted Ray, especially as they look very similar and the ranges overlap, so we sometimes informally refer to them as ‘Spundulates’.

Scientific Name: Raja undulata

Family: Rajidae

Maximum Size: 90cm (total length)

Diet: shrimps and crabs

Distribution: found around the eastern Atlantic and in the Mediterranean Sea.

Habitat: shelf waters down to 200m deep.

Conservation Status : As a commercially exploited species, the Undulate Ray is a recovering species in some areas. The good thing is that they have some of the most comprehensive management measures of almost any elasmobranch species, with both minimum and maximum landing sizes as well as a closed season. Additionally, targeting is entirely prohibited in some areas. They are also often caught as bycatch in various fisheries – in some areas they can be landed whilst in others they must be discarded.

IUCN Red List Status: Endangered

For more great shark information and conservation visit the Shark Trust Website

Image Credits: Banner – Sheila Openshaw; Illustration – Marc Dando

-

News3 months ago

News3 months agoHone your underwater photography skills with Alphamarine Photography at Red Sea Diving Safari in March

-

News2 months ago

News2 months agoCapturing Critters in Lembeh Underwater Photography Workshop 2024: Event Roundup

-

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs2 months ago

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs2 months agoCreature Feature: Swell Sharks

-

Blogs2 months ago

Blogs2 months agoMurex Resorts: Passport to Paradise!

-

Blogs2 months ago

Blogs2 months agoDiver Discovering Whale Skeletons Beneath Ice Judged World’s Best Underwater Photograph

-

Gear News3 months ago

Gear News3 months agoBare X-Mission Drysuit: Ideal for Both Technical and Recreational Divers

-

Gear Reviews2 months ago

Gear Reviews2 months agoGear Review: Oceanic+ Dive Housing for iPhone

-

Marine Life & Conservation2 months ago

Marine Life & Conservation2 months agoSave the Manatee Club launches brand new webcams at Silver Springs State Park, Florida