Marine Life & Conservation Blogs

Florida’s latest assault on sea turtles and why the global community should be concerned

Introduced by Jeff Goodman

In this time of dramatic climate change, habitat destruction, over fishing and species loss around the world, one would hope that governments and local authorities would be pro-active in legislation, education and direct action to address all these issues in a positive way. Ashamedly this is all too often not the case. A prime example of this is the plight of the Sea Turtles in Florida as witnessed and reported by Staci-lee Sherwood, Founder & former Director S.T.A.R.S. Sea Turtle Awareness Rescue Stranding , former founding member and staff Sea Turtle Oversight Protection & former staff at Highland Beach statewide morning survey program.

By Staci-lee Sherwood

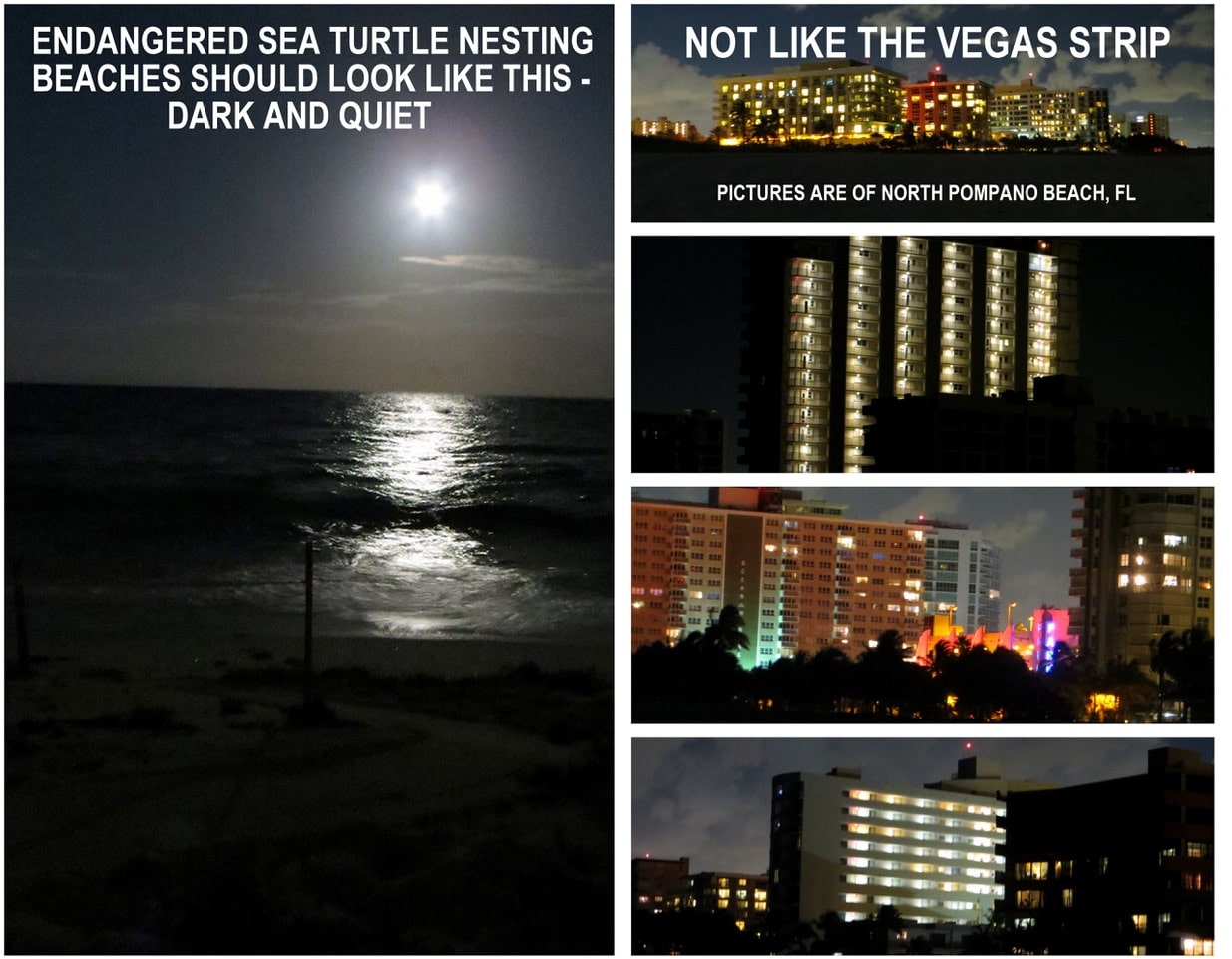

Florida is THE major nesting habitat for Loggerheads and one of the few places left for Leatherbacks. You would think being home to such endangered species Florida would work to ensure their survival but that’s not the case. In 2008 Richard and Zen Whitecloud were struck by how few hatchlings actually made it to the water because of all the light pollution from the land.

A nighttime rescue program was started in the hopes of saving any hatchlings that crawled toward all the artificial light that drew them like a powerful drug. Sea Turtles hatch and follow the bright sea horizon which for millions of years was the east blanketed by millions of shining stars and the moon. Not anymore, now the west is so illuminated by all the artificial lights the hatchlings think that is home and crawl towards it. They will follow the lights until they end up being run over by cars, fall into a storm drain or die from exhaustion and dehydration. Every morning the beaches throughout the state would be covered with death tracks going everywhere other then the ocean. This was no secret no mystery.

I

As far back as 1996 Dr Kirt Rusenko, who ran the Sea Turtle program in Boca Raton for over 25 years, stated “The lighting in Broward County is minimally better than it was 20 years ago” referring to the lack of local laws and abysmal enforcement or guidance from the state. “When I began work as Marine Turtle Permit Holder #041 in 1996, I thought the many sea turtle hatchling disorientation reports I sent to FWC would make a difference.” Time has shown that not to be the case. Death by light pollution is a global problem that negatively impacts many species.

The same year I joined this small dedicated group of rescuers I also started to work the morning survey on a state permit. This was the only program that actually had conservation elements to it. It involved recording any crawls and marking all new nests. I did this program everyday for 9 seasons while also doing the night time rescue program almost every night for 11 years. The morning survey was on Highland Beach, a very dark quiet beach where light pollution was kept to a dull roar and disorientation (DO) by hatchlings was a rarity. The hatchling tracks from the nest to the water went almost in a straight line, they did not fan out into a triangle. I saw thousands of nests over the years and it was always the same: straight to the ocean on Highland Beach but the tracks were all over the place in Broward and most of the other state beaches.

According to Sea Turtle Oversight Protection’s (S.T.O.P.) own data they have, to date, rescued approx 250,000 hatchings that would have died from light pollution in the past 10 years. That means they only rescue about 25,000 hatchlings a year or about 10% that disorientate. We know that Broward County has a disorientation rate of about 75% based on 10 years of record keeping while many other counties have an equal or greater light pollution problem. Because there is never anyone out there at night to save the hatchlings or record their death it’s easy to dismiss this and frame it as a local county problem and not a statewide problem. In Broward about 25% of all hatchlings that make it out of the nest actually make it on their own to the water. That means maybe 35-40% of all baby sea turtles make it to the water but only with a rescue and from there they face a toxic soup in polluted waters and a lifelong perilous journey. This was the nightmare I witnessed for 11 years. No other county has anyone out at night, no other Sea Turtle program involves nighttime rescue.

According to state data for 2020 they had a total of 133,493 nests (Loggerhead, Green and Leatherback). At a DO statewide rate of approx 50%, this could mean a loss of approx 6.671.650 hatchlings that could have made it to the water. Once in the water it’s estimated that hatchlings have a 1 in 10,000 chance to make it to adulthood. But first they have to get into the water.

In the modern era that is no longer feasible, even if the agency wanted to assist them there are just too many light sources. At such a low rate of survival it’s not sustainable long term; this species cannot survive by losing so many hatchlings. I have long felt that indoor hatcheries with a controlled temperature is the only chance to prevent or stave off extinction. This would allow hatchlings to emerge without losing millions to light pollution

In a 2020 permit holders meeting conducted by the state, they had a workshop of agencies and NGO’s about the light pollution problem. Not one person from any agency, not one person from any group had ever rescued a disorientated hatchling or been to Broward to see the rescue program, or had any firsthand in-the -field knowledge of the problem. Not one actual rescuer was involved but they should have been.

In utter disbelief to those rescue volunteers, the state decided to pull most of the permits S.T.O.P. had for their volunteers and end the program all together next year. This severe downsize is only for this year as next year rescue programs will cease and the death rate for hatchlings will soar once again. How will the turtles ever be able to hang on ?

In the words of a local resident who has seen first hand the work the rescuers do and understands the need to keep them: “These volunteers are a vital presence in our community; As residents, we urge the individuals responsible for permits to give thoughtful reconsideration of any plan that would reduce or impede the work of these volunteers.. As with these giant sea turtles, the overall impact of this volunteer effort is irreplaceable. Sincerely, Linda Thompson Gonzalez & Mario E. Palazzi.”

Many local residents chimed in that last year they “saw so many tracks in the morning that were going everywhere except the ocean.” It’s clear that these newborn Sea Turtle’s survival is tied to whether or not there is someone out there to pick them up and place them in the water

According to Casey Jones, founder of Sea Turtle Watch in Jacksonville: “It’s definitely going to be heartbreaking to lose hatchlings because of the volunteers not being able to be out there on the beach,” Jones explained. He said the focus needs to be on the bright lights that attract turtles to the land, which he claims, end with almost certain death. Like I said this is a statewide problem.

Many people who witness a Sea Turtle nest hatch for the first time can’t believe the light problem is that bad. Then suddenly a nest hatches and they all scamper in every direction. They suddenly cry out ‘OMG, catch them, hurry where did they go?’ Then they look at all those artificial lights, start counting all those nests and the numbers in their head start churning. Now they actually see how it could never be just a few hundred hatchlings or a rare occurrence but a nightly horror show that never ends.

If you would like to help please contact the following and politely ask they reinstate the rescue permits ASAP:

- Robbin Trindell admin sea turtle programs for Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission Robbin.Trindell@myfwc.com 850.922.4330

- Meghan Koperski signs off on all permits for Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission Meghan.Koperski@myfwc.com 561.575.5407

For more information about the plight of Florida’s Sea Turtles contact: Richard Whitecloud Director of S.T.O.P. on Whitecloud@seaturtleop.org

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs

Creature Feature: Dusky Shark

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

This month we’re taking a look at the Dusky Shark, a highly migratory species with a particularly slow growth rate and late age at maturity.

Dusky sharks are one of the largest species within the Carcharhinus genus, generally measuring 3 metres total length but able to reach up to 4.2 metres. They are grey to grey-brown on their dorsal side and their fins usually have dusky margins, with the darkest tips on the caudal fin.

Dusky Sharks can often be confused with other species of the Carcharhinus genus, particularly the Galapagos Shark (Carcharhinus galapagensis). They have very similar external morphology, so it can be easier to ID to species level by taking location into account as the two species occupy very different ecological niches – Galapagos Sharks prefer offshore seamounts and islets, whilst duskies prefer continental margins.

Hybridisation:

A 2019 study found that Dusky Sharks are hybridising with Galapagos Sharks on the Eastern Tropical Pacific (Pazmiño et al., 2019). Hybridisation is when an animal breeds with an individual of another species to produce offspring (a hybrid). Hybrids are often infertile, but this study found that the hybrids were able to produce second generation hybrids!

Long distance swimmers:

Dusky sharks are highly mobile species, undertaking long migrations to stay in warm waters throughout the winter. In the Northern Hemisphere, they head towards the poles in the summer and return southwards towards the equator in winter. The longest distance recorded was 2000 nautical miles!

Very slow to mature and reproduce:

The Dusky Shark are both targeted and caught as bycatch globally. We already know that elasmobranchs are inherently slow reproducers which means that they are heavily impacted by overfishing; it takes them so long to recover that they cannot keep up with the rate at which they are being fished. Dusky Sharks are particularly slow to reproduce – females are only ready to start breeding at roughly 20 years old, their gestation periods can last up to 22 months, and they only give birth every two to three years. This makes duskies one of the most vulnerable of all shark species.

The Dusky Shark is now listed on Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species (CMS), but further action is required to protect this important species.

Scientific Name: Carcharhinus obscurus

Family: Carcharhinidae

Maximum Size: 420cm (Total Length)

Diet: Bony fishes, cephalopods, can also eat crustaceans, and small sharks, skates and rays

Distribution: Patchy distribution in tropical and warm temperate seas; Atlantic, Indo-Pacific and Mediterranean.

Habitat: Ranges from inshore waters out to the edge of the continental shelf.

Conservation status: Endangered.

For more great shark information and conservation visit the Shark Trust Website

Images: Andy Murch

Diana A. Pazmiño, Lynne van Herderden, Colin A. Simpfendorfer, Claudia Junge, Stephen C. Donnellan, E. Mauricio Hoyos-Padilla, Clinton A.J. Duffy, Charlie Huveneers, Bronwyn M. Gillanders, Paul A. Butcher, Gregory E. Maes. (2019). Introgressive hybridisation between two widespread sharks in the east Pacific region, Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 136(119-127), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2019.04.013.

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs

Creature Feature: Undulate Ray

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

In this series, the Shark Trust will be sharing amazing facts about different species of sharks and what you can do to help protect them.

This month we’re looking at the Undulate Ray. Easily identified by its beautiful, ornate pattern, the Undulate Ray gets its name from the undulating patterns of lines and spots on its dorsal side.

This skate is usually found on sandy or muddy sea floors, down to about 200 m deep, although it is more commonly found shallower. They can grow up to 90 cm total length. Depending on the size of the individual, their diet can range from shrimps to crabs.

Although sometimes called the Undulate Ray, this is actually a species of skate, meaning that, as all true skates do, they lay eggs. The eggs are contained in keratin eggcases – the same material that our hair and nails are made up of! These eggcases are also commonly called mermaid’s purses and can be found washed up on beaches all around the UK. If you find one, be sure to take a picture and upload your find to the Great Eggcase Hunt – the Shark Trust’s flagship citizen science project.

It is worth noting that on the south coasts, these eggcases can be confused with those of the Spotted Ray, especially as they look very similar and the ranges overlap, so we sometimes informally refer to them as ‘Spundulates’.

Scientific Name: Raja undulata

Family: Rajidae

Maximum Size: 90cm (total length)

Diet: shrimps and crabs

Distribution: found around the eastern Atlantic and in the Mediterranean Sea.

Habitat: shelf waters down to 200m deep.

Conservation Status : As a commercially exploited species, the Undulate Ray is a recovering species in some areas. The good thing is that they have some of the most comprehensive management measures of almost any elasmobranch species, with both minimum and maximum landing sizes as well as a closed season. Additionally, targeting is entirely prohibited in some areas. They are also often caught as bycatch in various fisheries – in some areas they can be landed whilst in others they must be discarded.

IUCN Red List Status: Endangered

For more great shark information and conservation visit the Shark Trust Website

Image Credits: Banner – Sheila Openshaw; Illustration – Marc Dando

-

News3 months ago

News3 months agoHone your underwater photography skills with Alphamarine Photography at Red Sea Diving Safari in March

-

News3 months ago

News3 months agoCapturing Critters in Lembeh Underwater Photography Workshop 2024: Event Roundup

-

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs2 months ago

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs2 months agoCreature Feature: Swell Sharks

-

Blogs2 months ago

Blogs2 months agoMurex Resorts: Passport to Paradise!

-

Blogs2 months ago

Blogs2 months agoDiver Discovering Whale Skeletons Beneath Ice Judged World’s Best Underwater Photograph

-

Gear Reviews3 months ago

Gear Reviews3 months agoGear Review: Oceanic+ Dive Housing for iPhone

-

Marine Life & Conservation2 months ago

Marine Life & Conservation2 months agoSave the Manatee Club launches brand new webcams at Silver Springs State Park, Florida

-

News3 months ago

News3 months agoWorld’s Best Underwater Photographers Unveil Breathtaking Images at World Shootout 2023