News

The Whalesharks of Oslob

On our recent trip to the Philippines we were invited to visit the famous, but controversial, Whalesharks of Oslob. In the past, we had heard some negative reports about this experience and so it was with some trepidation that we agreed to go. First, we chatted to the team at Magic Island Dive Resort about what to expect. They told us that they used to boycott this experience themselves, as they had witnessed bad practices and only in the last few years, with tighter regulations being imposed, have they been taking their divers back to Oslob. With this expert local knowledge reassuring us, we packed up our camera gear and set off.

So, what goes on here? Well, for many years (some say over 100 years), way before it was a tourist attraction, fishermen have been feeding the Whalesharks that approach their boats, to keep them away from the nets and causing damage as they try to suck the tiny fish or shrimp through the small holes. In recent times, when people heard you could get up close with the magnificent fish, this practice started to bring in tourists. Now, the fishermen and the local village, make their livelihoods by selling tickets to see the Whalesharks. Tourists flock to Oslob in their thousands to get the chance to see and swim with the biggest fish in the sea.

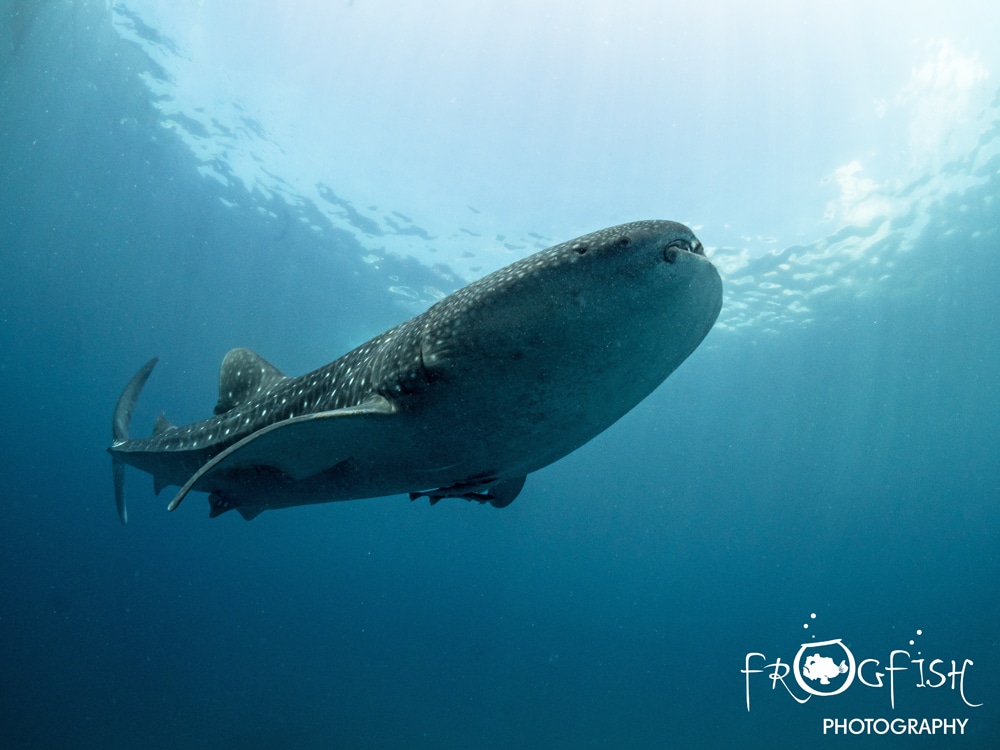

We had arranged to do a dive first, as Magic Island Dive Resort is an accredited dive centre for this experience, and they are one of only a handful that are allowed to go beneath the surface. We geared up well outside the protected zone, as boats with engines are not allowed, so we shore-dived and swam towards the main attraction. Soon we were marvelling at the Whalesharks above us as they approached the boats to be fed. Our guide counted 12 Whalesharks, and they were mostly small to mid-sized juveniles. Sometimes the Whalesharks would dive deeper and come in to inspect us before returning to the surface. Our group of five divers and two guides were the only divers in the water, and we had an hour to spend underwater (one of the many rules of diving here). From below, you get a completely different view of this experience, and we were amazed at just how few people got into the water with the gentle giants.

To see what this experience is all about though, we also wanted to join one of the boats to snorkel with the Whalesharks, which is what the majority of people who come here do. At first glance, it looks too crowded and we were worried about what we might encounter. We got into our boat that was paddled out to the main feeding arena. You only get 30 minutes and so we were ready to get in as soon as our boat was in position. The number of boats out on the water, as well as the number of feeders, corresponds to the number of Whalesharks in the bay on that day. As there were 12 sharks, it seems that there were about 12 tourist boats too, so perhaps around 100 people every half an hour (from day break to lunchtime) going to see them.

We were very surprised to see that most people just watched from the boat, or got into the water, but held onto the boat, so there were only a handful of people in the open water. This made it a much more pleasurable experience than we were expecting. We were given very strict instructions on not approaching the sharks: we could not use strobes, we were not allowed to wear sun cream and we were told that getting too close would see us getting a red card and sent out of the water. We were delighted to see that, when one snorkeler broke these rules, he was sent out of the water immediately. The Whalesharks themselves were incredible, slowly approaching to be fed, sucking the tiny fish from the water just in front of us, sometimes horizontal, and sometime positioned vertically in the water to feed. It is amazing to see.

We had heard stories of Whalesharks that had terrible injuries from the boats hitting them, but the boats here do not use engines and the only injury we saw was the bottom of a tail missing, which is unlikely to have been a propeller injury. We had heard stories of tourists grabbing or even riding the sharks, but this was not our experience at all. We had heard that the sharks never leave, but they are free to come and go and most only stay a few days and then move on, with one individual out of the hundreds that have been recorded here staying for over 300 days, in a very rare case.

As with many shark-feeding programs, the worry is that we are changing the behaviour of these Whalesharks by the very act of feeding them. There is a research organisation called LAMAVE that are based in Oslob and their researchers are in the water every day. They have a database of Whaleshark IDs so that they can monitor which individuals are visiting the site and for how long.

Whalesharks are a migratory species that follow their food sources around the globe. LAMAVE have discovered that a handful of Whalesharks stay much longer than would be normal in this area and so their behaviour has changed. Most, though, stay for a short period of time and then move on. Of course, Whalesharks may also mistake other boats, not in this protected area, as potential food sources and therefore be more prone to propeller strikes in the future. We only did one snorkelling session and did not see any bad behaviour from the snorkellers, apart from one, who was swiftly dealt with, so we hope that this side of people’s concerns have been reduced.

The local economy is now not based on fishing as it once was, but instead is based on showing tens of thousands of people these magnificent fish. There is a new school, hospital and infrastructure in the region, funded by the tourists that come here. We were delighted to see a boat of local school children pull up next to ours, and to observe their excitement at seeing Whalesharks for the first time, in the wild, was wonderful. The more people that fall in love with our seas, oceans and marine life, the more likely it is that they will protect it. Here, the Whalesharks are worth more alive than dead with their fins cut off; it is a trade-off that we can live with.

There is so much more we could write about this, but it will have to wait for another time. We were expecting our experience with the Whalesharks of Oslob to be a negative one, based on the stories we had heard, but in fact we came away having enjoyed it and we were re-assured that it is not a circus. This is not for everyone, that is for sure. It is not a wild encounter. We hope that the work of LAMAVE will continue to improve how the experience is run, so that the impact on the majestic Whalesharks is kept to a minimum, giving divers, tourists and locals alike a chance to see one of nature’s gentle giants up close.

For more information please have a look at the following websites:

Blogs

Northern Red Sea Reefs and Wrecks Trip Report, Part 3: The Mighty Thistlegorm

Jake Davies boards Ghazala Explorer for an unforgettable Red Sea diving experience…

Overnight, the wind picked up, making the planned morning dive a bit bumpy on the Zodiacs to the drop point on Thomas Reef. There, we would dive along the reef before descending through the canyon and then passing under the arch before ascending the wall with a gentle drift. The site provided great encounters with more pelagic species, including shoals of large barracuda, tuna, and bigeye trevally.

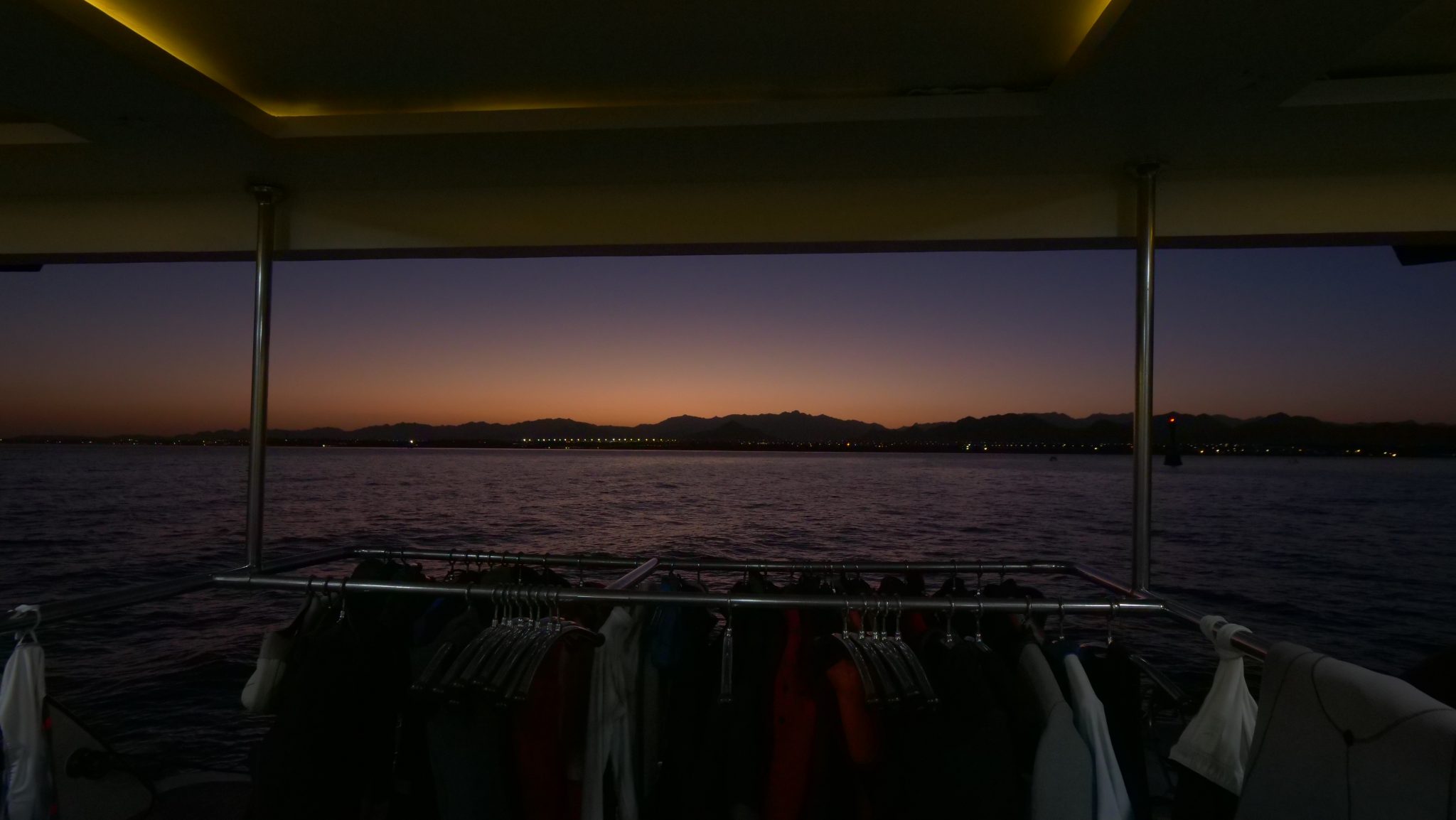

Once back on the boat, it was time to get everything tied down again as we would head back south. This time, with the wind behind us, heading to Ras Mohammed to dive Jackfish Alley for another great gentle drift wall dive before then heading up the coast towards the Gulf of Suez to moor up at the wreck of the Thistlegorm. This being the highlight wreck dive of the trip and for many onboard, including myself, it was the first time diving this iconic wreck. I had heard so much about the wreck from friends, and globally, this is a must on any diver’s list. Fortunately for us, there was only one other boat at the site, which was a rarity. A great briefing was delivered by Ahmed, who provided a detailed background about the wreck’s history along with all the required safety information as the currents and visibility at the site can be variable.

Kitting up, there was a lot of excitement on deck before entering the water and heading down the shoreline. Descending to the wreck, there was a light northerly current which reduced the visibility, making it feel more like the conditions that can be found off the Welsh coast. At 10m from the bottom, the outline of the wreck appeared as we reached the area of the wreck which had been bombed, as our mooring line was attached to part of the propeller shaft. Arriving on deck, instantly everywhere you looked there were many of the supplies which the ship was carrying, including Bren Carrier tanks and projectiles that instantly stood out.

We headed around the exterior, taking a look at the large propeller and guns mounted on deck before entering the wreck on the port side to take a look in the holds. It was incredible to see all the trucks, Norton 16H, and BSA motorcycles still perfectly stacked within, providing a real snapshot in time.

Overall, we had four dives on the Thistlegorm, where for all of the dives we were the only group in the water, and at times, there were just three of us on the whole wreck, which made it even more special, especially knowing that most days the wreck has hundreds of divers. Along with the history of the wreck, there was plenty of marine life on the wreck and around, from big green turtles to batfish, along with shoals of mackerel being hunted by trevally. Some unforgettable dives.

The final leg of the trip saw us cross back over the Suez Canal to the Gobal Islands where we planned to stay the night and do three dives at the Dolphin House for the potential of sharing the dive with dolphins. The site, which included a channel that was teeming with reef fish, especially large numbers of goatfish that swam in large shoals along the edge of the reef. These were nice relaxing dives to end the week. Unfortunately, the dolphins didn’t show up, which was okay as like all marine life they are difficult to predict and you can’t guarantee what’s going to be seen. With the last dive complete, we headed back to port for the final night where it was time to clean all the kit and pack before the departure flight the next day.

The whole week from start to finish on Ghazala Explorer was amazing; the boat had all the facilities you need for a comfortable week aboard. The crew were always there to help throughout the day and the chefs providing top quality food which was required after every dive. The itinerary providing some of the best diving with a nice mixture of wreck and reef dives. I would recommend the trip to anyone, whether it’s your first Red Sea liveaboard in the Red Sea or you’re revisiting. Hopefully, it’s not too long before I head back to explore more of the Red Sea onboard Ghazala Explorer.

To find out more about the Northern Red Sea reef and wrecks itineraries aboard Ghazala Explorer, or to book, contact Scuba Travel now:

Email: dive@scubatravel.com

Tel: +44 (0)1483 411590

Photos: Jake Davies / Avalon.Red

Blogs

Northern Red Sea Reefs and Wrecks Trip Report, Part 2: Wall to Wall Wrecks

Jake Davies boards Ghazala Explorer for an unforgettable Red Sea diving experience…

The second day’s diving was a day full of wreck diving at Abu Nuhas, which included the Chrisoula K, Carnatic, and Ghiannis D. The first dive of the day was onto the Chrisoula K, also known as the wreck of tiles. The 98m vessel remains largely intact where she was loaded with tiles which can be seen throughout the hold. The stern sits at 26m and the bow just below the surface. One of the highlights of the wreck is heading inside and seeing the workroom where the machinery used for cutting the tiles are perfectly intact. The bow provided some relaxing scenery as the bright sunlight highlighted the colours of the soft coral reef and the many reef fish.

Following breakfast, we then headed to the next wreck, which was the Carnatic. The Carnatic is an 89.9m sail steamer vessel that was built in Britain back in 1862. She ran aground on the reef back in 1869 and remains at 27m. At the time, she was carrying a range of items, including 40,000 sterling in gold. An impressive wreck where much of the superstructure remains, and the two large masts lay on the seafloor. The wooden ribs of the hull provide structures for lots of soft corals, and into the stern section, the light beams through, bouncing off the large shoals of glass fish that can be found using the structure as shelter from the larger predators that are found outside of the wreck.

The final wreck at Abu Nuhas was the Ghiannis D, originally called ‘Shoyo Maru,’ which was 99.5m long and built in Japan back in 1969 before becoming a Greek-registered cargo ship in 1980. The ship then ran aground on the reef on April 19th, 1983, and now sits at the bottom at a depth of 27m. Heading down the line, the stern of the ship remains in good condition compared to the rest of the hull. The highlight of the wreck, though, is heading into the stern section and down the flights of stairs to enter the engine room, which remains in good condition and is definitely worth exploring. After exploring the interior section of the ship, we then headed over to see the rest of the superstructure, where it’s particularly interesting to see the large table corals that have grown at the bow relatively quickly considering the date the ship sank. After surfacing and enjoying some afternoon snacks, we made sure everything was strapped down and secured as we would be heading north and crossing the Gulf of Suez, where the winds were still creating plenty of chop.

The next morning, it was a short hop to Ras Mohammed Nature Reserve for the next couple of days of diving. The 6am wake-up call came along with the briefing for the first site we would be diving, which was Shark & Yolanda. The low current conditions allowed us to start the dive at Anemone City, where we would drift along the steep, coral-filled wall. These dives involved drifts, as mooring in Ras Mohammed wasn’t allowed to protect the reefs. As a dive site, Shark & Yolanda is well-known and historically had a lot of sharks, but unfortunately not so many in recent years, especially not so early in the season. However, there was always a chance when looking out into the blue.

The gentle drift took us along the steep walls of the site, with plenty of anemone fish to be seen and a huge variety of corals. It wasn’t long into the dive before we were accompanied by a hawksbill turtle, who drifted with us between the two atolls before parting ways. Between the two reefs, the shallow patch with parts of coral heads surrounded by sand provided the chance to see a few blue-spotted stingrays that were mainly resting underneath the corals and are always a pleasure to see. With this being the morning dive, the early sunlight lit up the walls, providing tranquil moments. Looking out into the blue, there was very little to be seen, but a small shoal of batfish shimmering underneath the sunlight was a moment to capture as we watched them swim by as they watched us.

Towards the end of the dive, we stopped at the wreck of the Jolanda where the seafloor was scattered with toilets from the containers it was carrying. This provided a unique site to make a safety stop, which was also accompanied by a large barracuda slowly swimming by, along with a hawksbill turtle calmly swimming over the reef as the sun rays danced in the distance.

For the next dive, we headed north to the Strait of Tiran to explore the reefs situated between Tiran Island and Sharm El Sheik, which were named after the British divers who had found them. We started on Jackson before heading to Gordons Reef, where we also did the night dive. All the atolls at these sites provided stunning, bustling coral reefs close to the surface and steep walls to swim along, which always provided the opportunity to keep an eye out for some of the larger species that can be seen in the blue. Midwater around Jackson Reef was filled with red-toothed triggerfish and shoals of banner fish, which at times were so dense that you couldn’t see into the blue. Moments went by peacefully as we enjoyed the slow drift above the reef, watching these shoals swim around under the mid-afternoon sun.

The night dive at Gordon’s Reef was mainly among the stacks of corals surrounded by sand, which was great to explore under the darkness. After some time circling the corals, we came across what we were really hoping to find, and that was an octopus hunting on the reef. We spent the majority of the dive just watching it crawl among the reef, blending into its changing surroundings through changes in colour and skin texture. It’s always so fascinating and captivating to watch these incredibly intelligent animals, in awe of their ability to carry out these physical changes to perfectly blend into the reef. Before we knew it, it was time to head back to the boat to enjoy a well-deserved tasty dinner prepared by the talented chefs onboard.

Check in for the 3rd and final part of this series from Jake tomorrow!

To find out more about the Northern Red Sea reef and wrecks itineraries aboard Ghazala Explorer, or to book, contact Scuba Travel now:

Email: dive@scubatravel.com

Tel: +44 (0)1483 411590

Photos: Jake Davies / Avalon.Red

-

News3 months ago

News3 months agoHone your underwater photography skills with Alphamarine Photography at Red Sea Diving Safari in March

-

News3 months ago

News3 months agoCapturing Critters in Lembeh Underwater Photography Workshop 2024: Event Roundup

-

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs2 months ago

Marine Life & Conservation Blogs2 months agoCreature Feature: Swell Sharks

-

Blogs2 months ago

Blogs2 months agoMurex Resorts: Passport to Paradise!

-

Blogs2 months ago

Blogs2 months agoDiver Discovering Whale Skeletons Beneath Ice Judged World’s Best Underwater Photograph

-

Gear Reviews3 months ago

Gear Reviews3 months agoGear Review: Oceanic+ Dive Housing for iPhone

-

Marine Life & Conservation2 months ago

Marine Life & Conservation2 months agoSave the Manatee Club launches brand new webcams at Silver Springs State Park, Florida

-

News3 months ago

News3 months agoWorld’s Best Underwater Photographers Unveil Breathtaking Images at World Shootout 2023